If you are reading this, chances are you have just started a new training program or changed an aspect of your current training program, and things were going great.

But then, all of a sudden, you began to feel something in your knee(s) that started as a minor nuisance and then progressed to the point where getting down into a deep squat caused pain.

Knee pain during squats is an extremely common occurrence in active individuals and a phenomenon that I have seen multiple times as a Performance Physical Therapist and Strength and conditioning coach.

It is easy to forget how involved the knees are during training and take knees that are pain-free for granted.

I also had knee issues when I first began training that frustrated me and derailed my training progress for several weeks due to many factors I will cover in this article today.

Below, we will dive into the most common sources of knee pain during squats and then uncover various strategies and exercises I have used to help my clients and myself eliminate knee pain and keep it at bay once and for all.

TL;DR

Knee pain during squats typically comes down to a breakdown in the kinetic chain that puts forces on the knee joints they are unprepared for. It will also come about when sudden spikes in workload exceed the tissues’ capacity, such as in patellar and quadriceps tendinopathy.

Fixing knee pain during squats involves reducing the load on painful tissues and following a stepwise progression back to activity. This begins with a thorough assessment of your movement patterns, namely the squat pattern, identifying where faults exist, and prescribing corrective exercises such as eccentric training to correct imbalances.

Once tissues are fortified to withstand training demands, rehab concludes by incorporating this newfound tissue resiliency into functional movements that were once painful.

What Causes Knee Pain During Squats?

A variety of factors can cause knee pain. Knee pain with squatting is typically a result of improper mechanics or excessive workload, i.e., doing too much, too fast, and too soon.

I have touched on the joint-by-joint approach regarding back pain, which is also true for knee pain during squats.

When the hip and ankle are not functioning properly, it can cause issues at the knee joint that will compound over time until problems arise.

The soft tissue structures of the knee are also susceptible to overuse injuries with high volume or heavy squatting when they are not prepared to do so.

Knee Anatomy Review

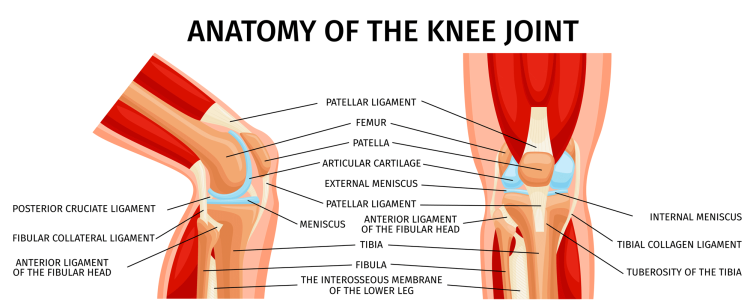

The knee joint comprises four bones — the femur, tibia, fibula, and patella, better known as the knee cap. All four bones combine to create three joints that comprise what most of us view as the knee joint.

These three joints are called the tibiofemoral joint, the proximal (close) tibiofibular joint, and the patellofemoral joint. All of these are critical for an optimal and pain-free squat pattern. When they become stiff or unstable, they can cause dysfunction and pain.

Below are the main structures of the knee joint, all of which provide stability and cushioning of impact for the knee during movements like squats.

Tendons:

- Quadriceps Tendon

- Patellar Tendon

- Hamstring Tendons

- Pes Anserine (gathering of several tendons into one junction)

Ligaments:

- Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL)

- Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL)

- Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL)

- Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL)

Meniscus

- Lateral Meniscus

- Medial Meniscus

Although these structures serve essential roles in optimal knee function, they can also be responsible for sources of knee pain in training.

Let’s dive into the most common sources of knee pain I have seen as a Performance Physical Therapist.

Patellar Tendinopathy

Patellar tendinopathy, also known as “jumper knee,” is a degenerative condition characterized by pain in the patellar tendon. The patellar tendon is a thick band of connective tissue that connects the patella, or knee cap, to the front of the tibia or shin bone.

Patellar tendinopathy occurs commonly in active individuals who perform repetitive jumping or sudden changes in direction (1). It can also be seen inside the gym during excessive box jumps, squatting, lunging, or any other movements requiring knee flexion.

Symptoms of patellar tendinopathy include pain and tenderness under the knee cap that is sometimes relieved at rest but can be exacerbated with a forceful contraction of the quadriceps muscle or rapid jumping or deceleration.

Tendon issues are usually caused by doing too much, too fast, and too soon. Folks who present with signs and symptoms of patellar tendinopathy will often describe getting back into the gym after time off, changing gym routines, or deciding to turn up the intensity of their session for an upcoming competition.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS), also referred to as “runner knee,” is a painful knee condition that involves pain at the front of the knee or behind the patella (2). PFPS is usually seen in active individuals who engage in high volumes of running, cycling, stair climbing, and squatting.

PFPS affects the area surrounding the kneecap and is associated with pain around the patella and/or a sensation of grinding or popping in the knee.

Muscular imbalances in the quadriceps, hamstrings, or hip muscles often cause PFPS. These can cause dysfunctional patellar tracking over the tibia and increased pressure at the knee cap from biomechanical faults. (2)

There may also be an uptick in squatting volume, such as if you just started a training program after being out of the gym for a while.

Lastly, movement faults in the lower body due to tightness or weakness that cause knee malalignment during movement, known as a valgus force, can contribute to PFPS. (2)

Quadriceps Tendinopathy

Quadriceps tendinopathy is very similar to patellar tendinopathy as it is a condition that involves pain, tenderness, and weakness of a tendon due to repetitive strain of overuse; however, the location of the pain is above the patella where the quadriceps muscle inserts. (3)

Quadriceps tendinopathy is common in active people who squat frequently since the quadriceps muscle is one of the primary movers during that motion. When the tendon performs work it is not prepared for, such as with high-volume training, it can become inflamed due to excessive microtears.

Many signs and symptoms of patellar tendinopathy are similar to quadriceps tendinopathy. These include pain with activities such as squats, jumping, or stairs and stiffness and swelling around the knee joint. (3)

Patellar Chondromalacia

Patellar chondromalacia is a condition that involves a softening and, ultimately, degeneration of the cartilage underneath the patella. (4)

This cartilage is a cushion for the patella to slide up and down a track called the trochlear groove on the tibia. When it is not present, bone-on contact can cause pain.

Patellar chondromalacia occurs from repetitive actions at the knee joint, such as excessive running, jumping, squatting, and other knee flexion activities. Like PFPS, a mal tracking due to muscular imbalances in the lower body can also lead to uneven forces on the patella and cartilage degradation over time. (4)

PFPS and patellar chondromalacia share similar signs and symptoms in that people typically feel pain in the front of the knee around the patella and a grinding sensation. (4)

Knee Bursitis

Bursitis is a condition caused by an irritation of the bursae, a small fluid-filled sac located in various locations in the knee joint. (5) These bursae provide a cushion between tendons and bones for smooth movement.

The four bursae that can become irritated at the knee include the prepatellar, the suprapatellar, the infrapatellar, and the pes anserine bursae. (5) They are typically irritated with repetitive stress, prolonged pressure, direct trauma, and poor mechanics during squatting. (5)

Bursitis symptoms include pain and tenderness localized around the affected bursae, limited range of motion, and swelling.

How To Fix Knee Pain During Squats

If you read through some of the most common causes of knee pain during squats, you will notice that although different structures are involved, what leads to pain is often similar.

For example, patellar tendinopathy involves pain and tenderness of the patellar tendon, while prepatellar knee bursitis affects the bursae sac under the knee cap. However, they are both caused by excessive repetition or workload and faulty biomechanics.

Pain and injury will typically result from load placed on structures they are not accustomed to handling. These forces can come from doing more repetitions than you have done recently, using more weight than you typically have, or moving poorly.

For example, when the knees cave in on squats, it causes an increase in the load placed on the patella.

This is why using progressive training principles and emphasizing your squat mobility in training is so important.

Let’s dive into how to address your knee pain if you cannot squat without it.

Offload Painful Tissues

Offloading the painful tissues of the knee is an essential first step in getting out of pain. There are instances where some pain is acceptable, but in most cases, you want to prevent aggravating inflamed structures.

By avoiding “picking the scab,” you can allow the tissues to begin the healing process.

Ways you can offload tissues and provide symptom relief include things like:

- Taping: Kinesiotape or mcconnel tape that can provide external support, improve patellar tracking, and increase proprioception at the knee. (2)

- Dry Needling: Inserting needles into specific trigger points or tight bands of muscles can improve muscle function and promote tissue healing.

- Orthotics: Orthotics can help offload tissue by improving biomechanics in the squat as you work to improve foot function. (2)

- Rest: Good old-fashioned rest is a great way to offload painful tissues. This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t train, but avoiding painful movements while you rehab can be a good idea until you can reintegrate the squat pattern into your training.

Optimize Mobility & Stability

Improving squat mobility is one of the first things I look for when treating athletes and folks who train frequently. Since our day-to-day is often spent sitting, it is common for the joints of the lower body to become stiff or tight, leading to poor form in the squats.

The joint-by-joint approach, popularized by Mike Boyle, demonstrates the importance of maintaining mobility throughout the body. As well as what can go wrong when it is not maintained.

The joint-by-joint approach describes alternating types of joints between mobile and stable joints throughout the body.

As the name implies, mobile joints must be able to move through an extensive range of motion. Stable joints need to stabilize to allow the mobile joints to move as they do.

Regarding the knee during squats, the ankle is mobile, the knee is stable, and the hip is mobile.

When the ankle and hip become stiff, the knee is required to move more than it is designed for, and this can cause dysfunction and pain over time.

Try these exercises to maintain mobility and stability in the lower body to fix or prevent knee pain during squats.

Hip CARs (Controlled Articular Rotation)

Tibial / Knee CARs (Knee Controlled Articular Rotation)

Ankle CAR (Controlled Articular Rotation)

Banded Leg Lowering

Eccentric and Isometric Training For Tendons

According to several studies, tempo training, such as using eccentric training in your squat training, can be very beneficial to both alleviating and preventing knee pain. (1) Specifically, if you are currently dealing with patellar or quadriceps tendinopathy.

Eccentric training involves intentionally lengthening the eccentric portion or the descent of the weight to the most disadvantageous position.

For a squat, this would be like descending the hips down to the ground slower than you would typically do. This increases the time under tension on the tendons, positively affecting their structure and strength.

A common eccentric protocol includes three sets of 15 repetitions of single-leg squats on a 25-degree angle, such as the Poliquin step-up.

Poliquin Step-Up

You can also use isometric training to strengthen the knee’s tendons. Isometrics can also have a pain-relieving effect on the painful tendons, allowing you to continue training while you rehab.

Isometric training involves statically holding a position for an extended period. For example, the research suggests holding the knee at 60 degrees of knee flexion for around 45 seconds for five sets under load.

This could be done using a band, leg extension machine, wall sit, or leg press.

I used this protocol when dealing with patellar tendinopathy, which helped me turn the corner on knee pain that was stopping me from training how I wanted to.

When I was done with the five sets, my tendon pain essentially vanished for about an hour — allowing me to continue to train and get great rehab sessions done.

Train Progressively

Once you are out of pain, it is time to get back into full squatting. But I cannot stress the importance of using a stepwise progression in your training. As I mentioned above, injuries happen when you do too much, too fast, too soon.

So, start by performing a squat variation that is less complex and for fewer repetitions and weight than you think you can do. You could start with a bodyweight squat, followed by a goblet squat, and then move to a front squat. Then, add a little more work each week as long as you feel good and are recovering.

A great way to move from the eccentric and isometric exercises into full squatting again with a barbell is to incorporate a protocol called “Heavy Slow Resistance” (HSR).

An HSR protocol entails using heavier weights and purposely moving at a slower tempo throughout the full range of the squat.

So, a controlled descent is followed by an intentionally slow ascent back to full standing; then, the load is increased weekly to strengthen the tendon.

Wrapping Up On Knee Pain and Squats

You can see how much can go into the cause and solutions for knee pain-related squatting. In almost every instance of knee pain in clients I have worked with, there is some connection to a change in workload for their training.

Sometimes, it’s because they finally decided to get off the couch and into the gym but were not working with a professional and mismanaged their work. Or, they allowed their form to go unchecked and ultimately sustained an overuse injury.

Regardless of why you may suffer from knee pain, you now have the knowledge and strategies to help get yourself out of pain and back to squatting again.

It is important to note that there are instances where knee pain with squatting is not related to overuse and can be structural, such as with meniscus tears. In this instance, please seek a licensed medical professional for a thorough evaluation.

If you are not currently dealing with knee pain, you still have all the tools to manage it if it does show its ugly face or if you wish to incorporate these strategies and exercises into your current training program to keep training pain-free for years to come.

So, let’s get you back to squatting again!

References:

- Figueroa, D., Figueroa, F., & Calvo, R. (2016). Patellar Tendinopathy: Diagnosis and Treatment. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 24(12), e184–e192.

- Petersen, W., Ellermann, A., Gösele-Koppenburg, A., Best, R., Rembitzki, I. V., Brüggemann, G. P., & Liebau, C. (2014). Patellofemoral pain syndrome. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA, 22(10), 2264–2274.

- King, D., Yakubek, G., Chughtai, M., Khlopas, A., Saluan, P., Mont, M. A., & Genin, J. (2019). Quadriceps tendinopathy: a review-part 1: epidemiology and diagnosis. Annals of translational medicine, 7(4), 71.

- Zheng, W., Li, H., Hu, K., Li, L., & Bei, M. (2021). Chondromalacia patellae: current options and emerging cell therapies. Stem cell research & therapy, 12(1), 412.

- Rishor-Olney, C. R., & Pozun, A. (2022). Prepatellar Bursitis. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

Tip: If you're signed in to Google, tap Follow.