Along with the deadlift, the squat is the ultimate test of lower extremity strength and power.

There are few exercises that develop the glutes, quads, hamstrings, and core, as effectively as the squat.

For many avid lifters, improving squat performance is high on the priority list. One of the major factors in squat performance is the technique or style that is used.

This article will review two popular squatting techniques to allow you to determine the method that will be most beneficial.

The Powerlifting Squat

When setting up for the powerlifting squat, the barbell should be placed below your upper traps. This is often referred to as the “low-bar” squat.

Not only does using the low-bar position give the lifter a mechanical advantage, but it also allows the trunk to lean forward and engage more of the powerful posterior muscles such as the glutes and hamstrings (1).

Typically, a wide stance is assumed during a powerlifting squat which causes the range of motion to be restricted.

In a powerlifting competition, for a squat to be considered a good lift you must reach parallel or slightly below. Therefore, although the stance is wide it should still allow you to hit parallel.

A combination of the low bar position and restricted range of motion allows for the greatest amount of weight to be squatted.

This is evidently significant as the ultimate goal in powerlifting is to lift as much weight as possible.

While there are many extremely strong squatters who use other styles, the majority of squat world records use the powerlifting style.

Powerlifting Squat Technique:

- Begin with the feet much wider than the hips with the feet turned out

- Grasp the bar using a width that is most comfortable for you

- Place the bar on the “shelf” of the shoulder blades

- Lift the chest, engage the core muscles and unrack

- Drop the hips back and down while keeping the knees out

- Descend to parallel before powerfully driving back up

The Olympic Squat

Unlike the powerlifting squat, the Olympic squat starts with a high-bar position. This is where the bar sits on the upper traps rather than below.

This position does not allow the trunk to tip forward nearly as much and more closely replicates the trunk position assumed during the snatch or clean (2).

As a result of the more vertical trunk position, the glutes, quads, and trunk stabilizers become highly activated. Meanwhile, the demand lessens on the hamstrings.

Foot position also differs. Instead of being extremely wide, the Olympic squat places the feet just wider than hip-width with toes either pointed straight or turned out slightly.

This increases the range of motion and allows the lifter to drop deeper. This is essential in the snatch and clean where the lifter must rapidly drop down low in order to catch the bar.

A common squatting coaching cue is to prevent the knees from passing over the toes. However, considering the range of motion, it is possible that this will occur, especially with tall lifters.

Providing proper form is adhered to, there is no danger in allowing the knees to pass over the line of the toes (3).

Taking into account the high-bar position and large range of motion, significantly less weight can be lifted with the Olympic squat in comparison to the powerlifting squat.

Olympic Squat Technique:

- Start with the feet slightly wider than hips with toes pointed forwards or slightly out

- Grasp the bar just wider than shoulder-width

- Place the bar on the upper back

- Lift the chest, engage the core muscles and unrack

- Drop the hips back and down while keeping the knees out

- Descend as far as possible with good form before powerfully driving back up

Which Technique Is Best For Squats?

Ultimately, neither technique is better than the other. It entirely depends on your goals, needs, limitations, and preferences.

The Olympic squat can be considered the “natural” squat. It uses a full range of motion and mirrors how the body naturally moves.

A great example that highlights this can be found in babies and toddlers. Infants can sit in a deep squat position for a prolonged time period without any issue.

However, as adults, the Olympic squat can be a little more complex to learn than the powerlifting squat as it has greater mobility demands.

When learning the Olympic squat, a common area that can cause issues is the ankles as a large degree of dorsiflexion is required for this squatting style.

The reason why the weightlifting shoes worn by Olympic lifters have an elevated heel is to increase the amount of dorsiflexion and enhance the range of motion.

With the powerlifting squat, however, a great level of mobility and dorsiflexion is not required. This explains why many powerlifters typically wear zero drop shoes rather than weightlifting shoes.

As reflected on, the bar position, foot position, and mobility, all influence the demands and range of motion of the squat.

For the majority of individuals, the powerlifting squat will allow you to squat heavier weight, however, the Olympic squat utilizes a larger range of motion.

Consider the benefits and drawbacks of each style before concluding which one is best for you.

If you are interested in squatting the most weight possible, the powerlifting squat may be the best choice.

However, if this is not of utmost importance, the Olympic squat may be the better choice. While slightly more technically challenging, it can improve strength, mobility, and athleticism.

Here is another great comparison

Optimizing Your Squat

Although the earlier section provided detail on each squatting style, understand that these are only guidelines.

In reality, there are no strict rules for squatting. There are a variety of factors that influence how you move and, therefore, the way in which you squat is likely unique.

Therefore, often a little bit of experimentation is needed to determine what works best for you. Some lifters even have experienced success by combining elements of both styles.

Furthermore, some training programs prescribe both squatting styles into the same plan and still have yielded excellent results.

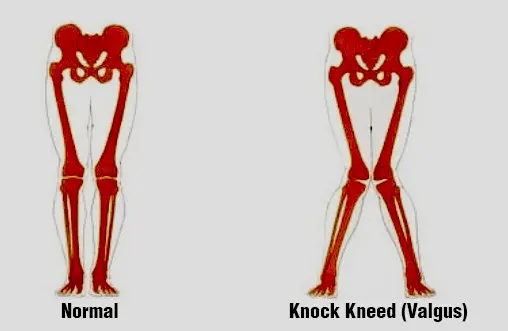

That said, it is not recommended to perform the powerlifting squat with a high-bar position as this may increase knee valgus.

Knee valgus is where the knees cave in rather than staying wide and over the top of the feet. Excessive knee valgus can cause a serious injury to the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee (4).

The very wide stance utilized in a powerlifting squat and the upright trunk position assumed with a high-bar position may increase the risk of knee valgus.

Furthermore, raising the bar higher increases the lever arm and, consequently, puts additional strain through the lower back.

While there are powerlifters who squat in this manner, it is generally not recommended.

Briefly, one final note on foot position and where your toes should be pointing.

It has been suggested by some weightlifters that the toes should remain pointed straight at all times.

The thought behind this is that by keeping toes pointed forward you can most effectively stabilize the joints of the lower extremities while enhancing torque generation.

However, by simply assessing the lifts of elite Olympic lifters, you will see that the majority turn the feet out to a degree.

That said, there are no right or wrong answers when it comes to squatting. If preventing turnout is beneficial for you, by all means, utilize it.

Final Word

Although squatting styles are typically categorized as either “Powerlifting” or “Olympic”, there is little benefit to be found in being rigid with your technique.

Often optimal squatting comes as a result of experimentation and practice and may even combine elements of both squatting styles.

References:

1 – Glassbrook, Daniel J.; Helms, Eric R.; Brown, Scott R.; Storey, Adam G. (2017-09). “A Review of the Biomechanical Differences Between the High-Bar and Low-Bar Back-Squat”. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 31 (9): 2618–2634. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002007. ISSN 1533-4287. PMID 28570490.

2 -Glassbrook, Daniel J.; Brown, Scott R.; Helms, Eric R.; Duncan, Scott; Storey, Adam G. (2019-07). “The High-Bar and Low-Bar Back-Squats: A Biomechanical Analysis”. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 33 Suppl 1: S1–S18. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001836. ISSN 1533-4287. PMID 28195975.

3 – Fry, Andrew C.; Smith, J. Chadwick; Schilling, Brian K. (2003-11). “Effect of knee position on hip and knee torques during the barbell squat”. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 17 (4): 629–633. doi:10.1519/1533-4287(2003)0172.0.co;2. ISSN 1064-8011. PMID 14636100.

4 – Utturkar, G. M.; Irribarra, L. A.; Taylor, K. A.; Spritzer, C. E.; Taylor, D. C.; Garrett, W. E.; DeFrate, Louis E. (2013-1). “The Effects of a Valgus Collapse Knee Position on In Vivo ACL Elongation”. Annals of biomedical engineering. 41 (1): 123–130. doi:10.1007/s10439-012-0629-x. ISSN 0090-6964. PMC 3647681. PMID 22855117.

Tip: If you're signed in to Google, tap Follow.