Calorie counting has, since the 1980s, effectively dominated the bodybuilding industry. Where weight lifters and physique competitors in the first half of the twentieth century maintained their weight through rough estimations of their food intake, individuals today are far more focused, and some would argue obsessed, with managing, quantifying and restricting their food intake. That many individuals not interested in stepping on stage use calorie-tracking apps on their smartphones suggests that this interest has spilled over from the fitness industry into more mainstream aspects of everyday life.

As someone who religiously tracks their calories and macronutrients, the idea of monitoring my diet in this manner has often been unproblematic. Everyone I know does it, so it seems completely normal. This is despite the fact that the mere act of acknowledging calories only began in the nineteenth century. In a short space of time century – relative that is to human existence, the calorie has gone from being a scientific denotation to a part of everyday life.

The purpose of today’s article is not to rage against the caloric machine or to evaluate the benefits of such an approach, the latter of which can be found in many of Fitness Volt’s previous posts. Instead, today’s post discusses the history of calorie counting, from its discovery at the beginning of the twentieth century to the present day.

Inventing the Calorie

Although it seems odd to consider, the idea of calories is not a time-honored tradition. It is, in fact, a relatively new and novel concept in human dietetics. Previously individuals have cited the creation of the term calorie to the mid-1850s when it was used in relation to heat and temperature. More recent work, however, has traced its history back to the early 1820s in France [1]. Between 1819 and 1824, it is said that French physicist and chemist Nicholas Clément introduced the term calories in lectures on heat engines to his Parisian students. His new word, ‘Calorie’, proved popular and by 1845, the word appeared in Bescherelle’s Dictionnaire National, the first time the term appeared in such a public forum.[2]

Importantly, the idea of the calorie quickly took hold among the scientific community. At a time when many sciences were still in their infancy, and the idea of a professional class of physicians and scientists was still controversial, the calorie became an accepted term and concept among a growing scientific class. By the end of the 1860s, the term calorie had migrated from France across most of Western Europe. It was during this time that translations of Adolphe Ganot’s French-language work on physics, which included the term calorie, was translated into several other European languages, including English. Ganot’s work was significant as it was one of the first works to define calories akin to modern understandings [3]. According to Ganot, the term calorie was used to describe the heat needed to raise the temperature of 1 kg of water from 0 to 1°C. This definition will not be on the test, but it is always worth remembering that the term calorie is scientific and related to heat, which makes the term ‘bad calories’ somewhat confusing to the scientifically minded.

Returning to the growing use of the term calorie, the term’s next significant moment came in the late nineteenth century when American Professor Wilbur O. Atwater introduced the term to the American public [4]. While it is difficult to pinpoint exactly where Atwater was introduced to calories, James Hargrove’s work on the subject suggests that Atwater was familiar with the term owing to his medical studies in Germany.[5] Significantly, Atwater wrote on the calorie, and its relation to food, in popular magazines like Century Magazine and the Farmer’s Bulletin. Atwater’s articles came at a time when the US Congress was becoming increasingly interested in the quality and quantity of American food.[6]

At a time when several foods were being contaminated, most notably milk, and few ideas as to the ‘ideal’ diet existed, Congress felt a national imperative to learn more about the food itself.[7] Accordingly, Atwater was hired by the newly created Storrs Agricultural Experiment Station, to study the constituents of dozens of foods at a molecular level. From the 1890s, Atwater and his team at Wesleyan undertook an exhaustive study into the caloric content of over 500 foods with the intent of producing a scientific and healthy way of maintaining one’s weight.[8] Unsurprisingly, Atwater’s study and its results made Atwater a leading authority on nutrition as well as elevating the importance of the calorie in the common diet. In 1902, Atwater released one of his many books on nutrition aimed at describing a healthy diet. At this time the advice was simple – don’t overeat and keep some sort of balance in your diet:

Unless care is exercised in selecting food, a diet may result which is one-sided or badly balanced that is, one in which either protein or fuel ingredients (carbohydrate and fat) are provided in excess … the evils of overeating may not be felt at once, but sooner or later they are sure to appear perhaps in an excessive amount of fatty tissue, perhaps in general debility, perhaps in actual disease.[9]

Calorie Counting and Weight Loss

Atwater helped popularise the calorie and a moderate diet but who first related strict calorie counting to weight loss? The answer lies not in a bodybuilder or physical culturist but rather with the American physician, author, and philanthropist, Lulu Hunt Peters.[10] The First World War (1914-1918) had seen severe food shortages around large parts of the globe and, as a result of this, an interest in ensuring an adequate intake of calories. In 1918, Lulu Hunt Peters took the opposite approach and began advocating calorie counting as a means of weight loss. The timing could not have been more opportune.

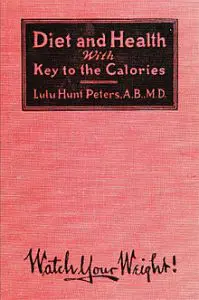

Heather Addison’s work on Hollywood and physical culture found that during the early to mid-1920s, American society, particularly female society, became obsessed with weight loss. Striving to possess the same bodies as their favorite Hollywood stars, American citizens, and those in other countries undertook a series of extreme weight loss diets to achieve this look.[11] Calorie counting was one such approach but one that was at least based in science. So from the late 1910s and well into the 1920s, Peters wrote a number of newspaper columns for the Central Press Association entitled ‘Diet and Health’, which dealt with issues of health and weight.[12] Proving popular with her audience, namely middle-aged American women, Peters was encouraged to collect her writings into one easily digestible volume, something she did in 1918.

Entitled Diet & Health: With Key to the Calories, Peters published her first and only book on calorie counting. Published with the subheading of ‘Watch Your Weight’, Diet & Health was one of the first ‘modern’ dieting books to truly strike a chord with the American public. From 1922 to 1926, it was a top ten non-fiction bestseller in American markets. That people likely bought a shared the book, or at least, its advice with others suggests that the market was even bigger than its card topping success suggests. Peters’ success was predicated on a number of factors, specifically, its simplicity, empathy and its success.[13]

Regarding its simplicity, Peters took the calorie, a term which although popular, was still shrouded in the mystique of scientific enquiry and made it accessible for a mass audience. Accordingly, Peters told readers that each day they had a certain amount of calories to spend on food. Food would no longer be understood in portion sizes or taste, but rather in calories, Hence bread was no longer depicted in slices but rather, 100 calories per portion. Peters’ easy to understand advice made the practice far more accessible than before. Coupled with this, Peters displayed an innate understanding of the psychology underpinning successful weight loss. It was for this reason that her diet books also discussed the importance of one’s peer group, family and food environment in supporting one’s weight loss goals.[14]

In this manner, the book proved remarkably ahead of its time, as scholars still cite the importance of these factors in weight loss. Finally, Peters’ diet was remarkably effective, if adhered to. Readers were told to eat roughly 1,200 calories a day from whatever food group they desired. The only exception to this was candy which Peters advised against, believing it too easy to binge on. On her own weight loss transformation, Peters informed readers she herself had weighed upwards of 200 lbs. before dropping 50-70 lbs. eating this way.[15]

For athletes and bodybuilders, Peters’ advice on gaining and losing weight was likewise ahead of its time. To calculate your basic caloric needs, she recommended multiplying your body weight by 15-20 to find the magic number. If you needed to lose weight eat 200-1000 calories less and to gain weight eat 200-1000 calories more. Peters’ advice on gaining weight through calorie counting suggests her familiarity with muscle building and lifters but, remarkably, it took several decades for calorie counting to become a recognizable behaviour for bodybuilders.

Bodybuilding and Calorie Counting

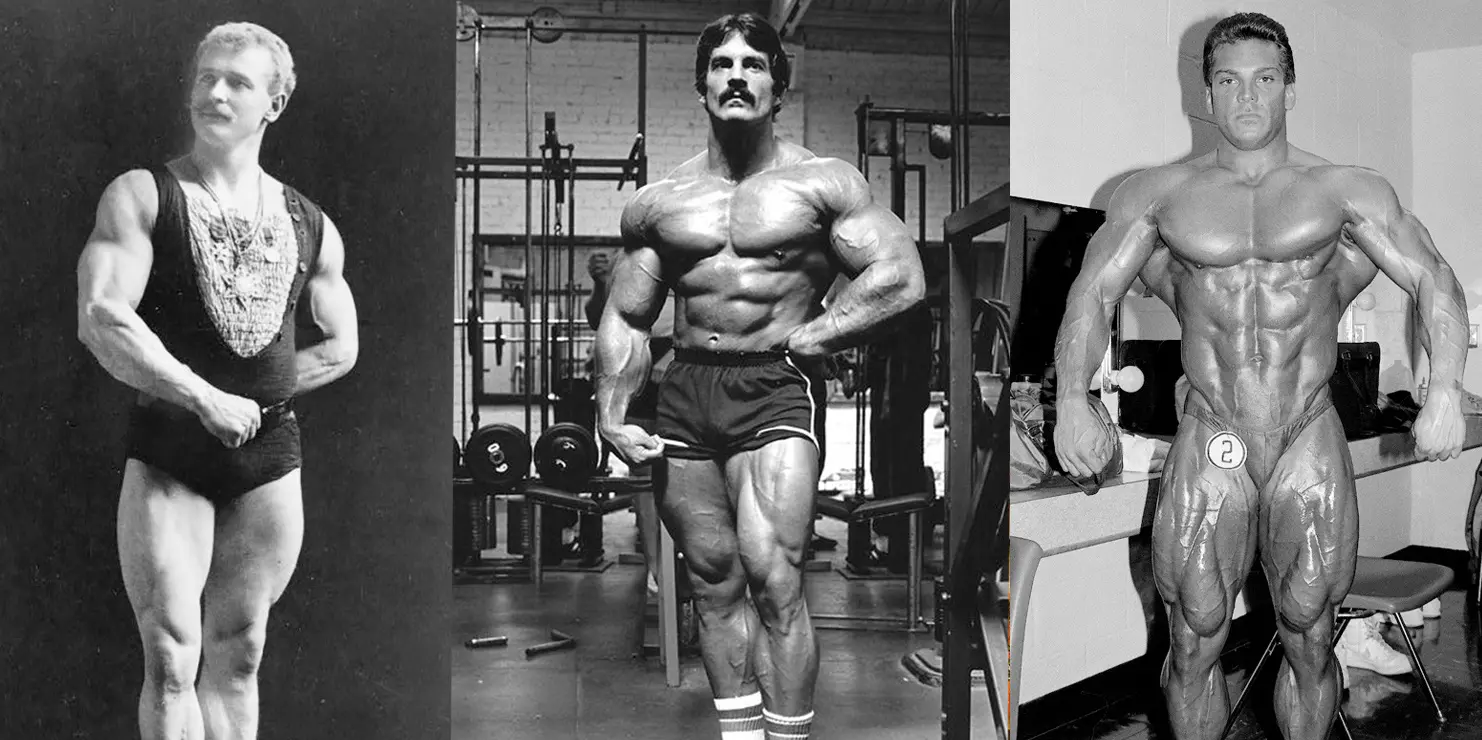

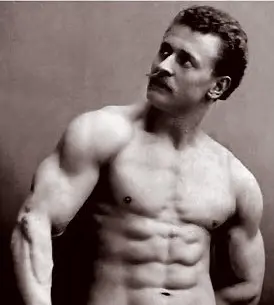

Given that calorie counting became a recognized means of dieting from the 1910s, it’s remarkable to read that bodybuilders were very slow to use calorie counting to cut down for competition. The early forerunners of modern bodybuilding, men like Eugen Sandow or George Hackenschmidt, did not advocate calorie counting for health.[16] Instead they chose to promote eating a whole and varied diet. It was sound advice but not the extreme forms of eating we associate with physique sports. Even those at the mid century, men like Reg Park or John Grimek, focused more so on the overall quantity of their diets, rather than its caloric composition.[17] Accordingly, when someone like Park or Grimek cut down for a competition, they simply reduced the overall amount of food that they ate. In the 1960s and early 1970s, the most popular diet for competitive bodybuilders was some form of a ketogenic diet. This came in the form of Vince Gironda’s ‘steak and eggs’ diet, Rheo H. Blair’s ‘meat and water’ diet or some combination thereof.[18] Arnod Schwarzenegger’s nutrition coach, John Balik promoted the ketogenic diet in his wonderfully titled ‘You Can’t Flex Fat!’.[19]

So when did calorie counting first emerge in the bodybuilding world? One of the first examples came in 1973 with Arthur Jones, the founder of the High-Intensity Training movement associated with Nautilus machines. Seeking to demonstrate both the effectiveness of his training methods and his machines, Jones and Casey Viator, then a young but highly successful bodybuilding, ate 800 calories a day for several weeks before upping their intake to around 5,000 calories a day during their training. Dubbed the ‘Colorado Experiment’, Jones and Viator shocked the bodybuilding world with claims of 40 pound plus muscle gains in just a month.[20]

Jones’ disciple, Mike Mentzer, took calorie counting to a more scientific level. As part of his 1979 Mr. Olympia prep, at which Mentzer won the over 200 lbs. Category, Mentzer used a strict calorie counting regimen. Recollecting sometime later about his prep, Mentzer advocated a sort of ‘If It Fits Your Macros Approach’, whereby his 2000 a day calorie intake included ice cream and pancakes![21] From Mentzer’s railing against ketogenic diets, later bodybuilders took note. In the 1980s, Rich Gaspari and Lee Labrada used calorie counting to build their now-legendary physiques.

Gaspari, in particular, was greatly influential. In 1988, Rich Gaspari revealed to the makers and viewers of Battle for The Gold, a bodybuilding documentary, that he calculated his caloric intake to the tee, weighing everything and generally eating an incredibly strict diet.[22] To prove his seriousness, Gaspari then showed viewers his nutritional calorie tables which accompanied him at every meal.

By then, Gaspari was known for his shredded and defined physiques which, arguably helped to change the very course of bodybuilding. At the 1986 IFBB Pro World contest, Gaspari exhibited a new, and previously unprecedented of leanness. Unlike previous bodybuilders, Gaspari exhibited visibly striated glutes.[23] While this may seem incidental to those who have never competed, the sign of striated glutes is a sure and obvious sign of extreme leanness.

For later bodybuilders, striated glutes became the new standard expected in competition. Long before hip thrusts got the lifting community concerned about their glutes, Gaspari had bodybuilders thinking about their behinds. In a desperate bid to mimic Gaspari, calorie counting became the norm among bodybuilders. From the 1980s onward, calorie counting became the accepted means of bulking and cutting in the sport. What began in a lab eventually entered the gymnasium.

References

- Jou, Chin. “The Progressive Era Body Project: Calorie Counting and Discipling the Stomach in 1920s America.” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era (2018) 1-19.

- Hargrove, James L. “History of the calorie in nutrition.” The Journal of nutrition 136, no. 12 (2006): 2957-2961.

- Cullather, Nick. “The foreign policy of the calorie.” The American Historical Review 112, no. 2 (2007): 337-364..

- Hargrove, “History of the calorie in nutrition.”.

- Hargrove, “History of the calorie in nutrition.”.

- Cullather. “The foreign policy of the calorie.”

- Atwater, W. O., and A. P. Bryand. “Connecticut (Storrs) Agricultural Experiment Station.” 12th Annual Report, Storrs, CT (1980): 73-123.

- Nichols, Buford L. “Atwater and USDA nutrition research and service: a prologue of the past century.” The Journal of nutrition 124, no. suppl_9 (1994): 1718S-1727S.

- Ibid.

- Veit, Helen Zoe. “‘So few fat ones grow old’: diet, health, and virtue in the golden age of rising life expectancy.” Endeavour35, no. 2-3 (2011): 91-98.

- Addison, Heather. Hollywood and the rise of physical culture. Routledge, 2003.

- Peters, Lulu Hunt. Diet and Health with Key to the Calories. Reilly and Lee, 1922.

- Katz, David. “Health: The medicalization of fat.” Nature 510, no. 7503 (2014): 34.

- Peters, Diet, and Health.

- Ibid.

- Gilman, Sander L. Diets and dieting: A cultural encyclopedia. Routledge, 2008.

- Roach, Randy. Muscle, smoke, and mirrors. Vol. 1. AuthorHouse, 2008.

- Heffernan, Conor. “Before the Carnivore Diet”. Physical Culture Study. https://physicalculturestudy.com/2019/06/03/before-the-carnivore-diet-rheo-h-blairs-meat-and-water-diet-1960s/.

- Balik, John. You Can’t Flex Fat. Santa Monica, 1979.

- Jones, Arthur. “The Colorado Experiment.” Iron Man (1973): 34-37.

- Mentzer, Mike. Heavy duty. ABM-Fitness-und Kraftsport-Verlag, 1979.

- “The Battle For Gold.” Video 4, 1988.

- Heffernan, Conor. “All a Load of Pants? Posing Trunks in Male Bodybuilding Part Twp”. Playing Pasts. https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/physical-culture/all-a-load-of-pants-posing-trunks-in-male-bodybuilding-part-two/.

Tip: If you're signed in to Google, tap Follow.