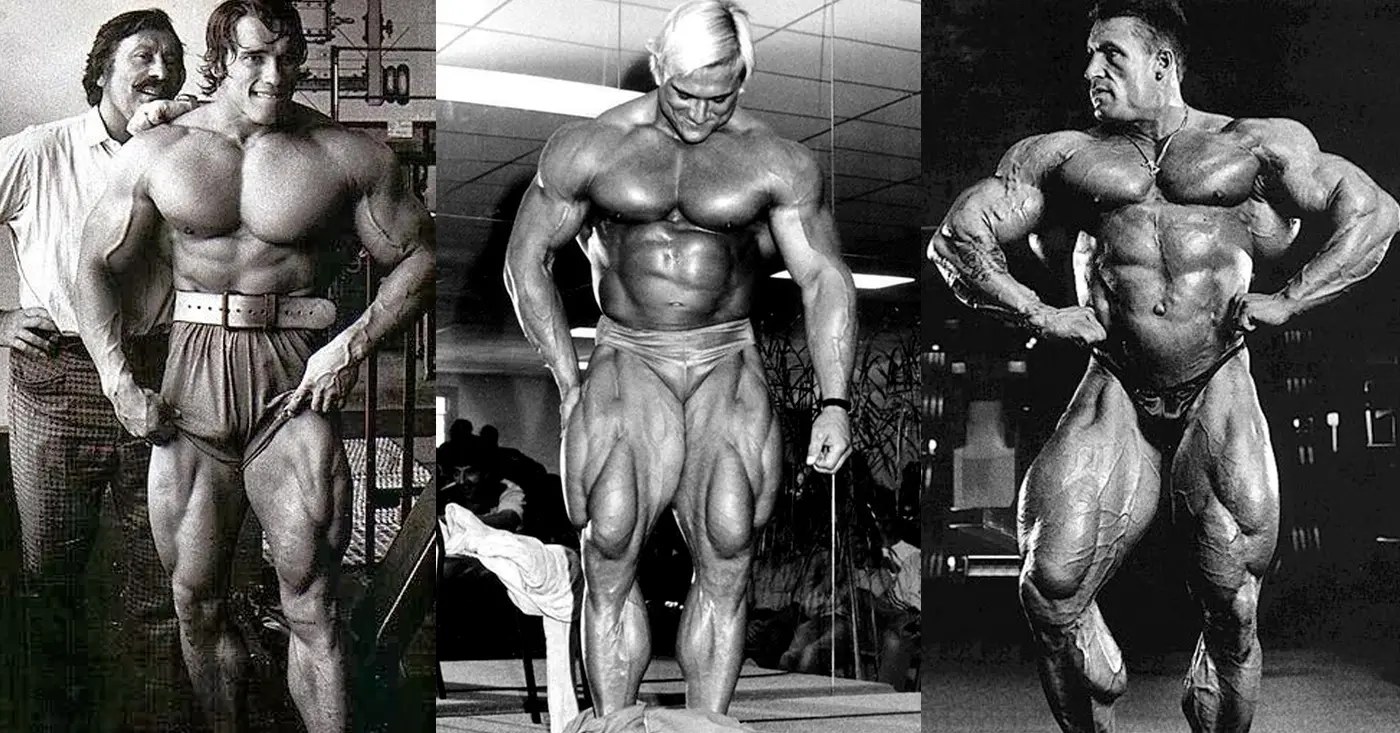

Thick and muscular legs are a true symbol of strength.

Although guys may get caught up in the idea that you need big arms, a big chest and a wide upper back, the fact is that none of that is relevant without a sturdy pair of legs supporting them.

Unfortunately, growing the legs can be a painful experience.

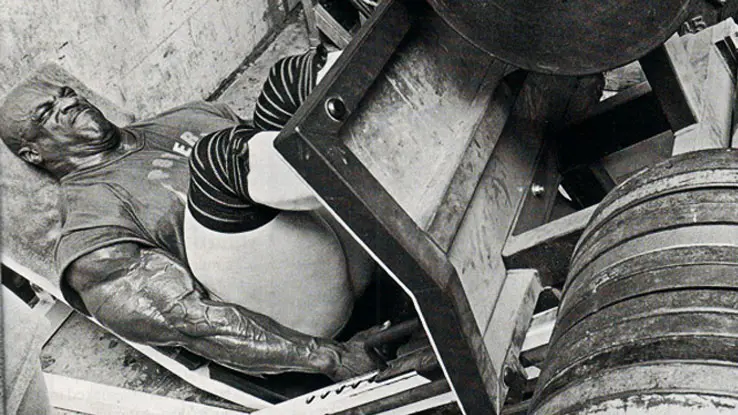

With some of the largest muscle groups residing in the lower body, you will need to get comfortable lifting heavy weights, tolerating astronomically high levels of lactate, and the occasional agony of crippling DOMS.

So it’s no wonder that guys only take their leg growth to a certain point, before abandoning further development.

However, in this article, I want to spin lower body training on its head and give you a different approach to building up your lower body.

There are 2 reasons for this: –

Firstly, if you’ve actively been trying to build up the size of your thighs, but have produced minimal return, then it’s always good to try a different method.

As Einstein famously quoted:

“The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again….but expecting a different result.”

Secondly, if you’ve developed a distaste for uncomfortable leg training and are unwilling to really push the envelope, then experimenting with a different method may feel a lot less daunting.

Not only that, but if it’s a previously untried method, then it may trigger powerful growth with little effort, making it a great return on investment.

Muscle Hypertrophy

Before I dive into the meat of this article, I want to quickly go over the mechanisms of muscular hypertrophy.

Schoenfeld (2010) uncovered 3 ways in which muscular hypertrophy is triggered:

- Mechanical Tension

- Muscle Damage

- Metabolic Fatigue

The level to which is most effective may be dependent on the training age of the individual.

For example, a beginner with no training experience will benefit the most using methods that generate the highest levels of muscular tension i.e. lifting heavy weights through a full range of motion. Should they focus on metabolic fatigue methods i.e. ‘pump’ training, the working weights would be so light that only a minimal effect on muscle growth would be achieved.

However, a lifter with over a decade of training experience, and whose body has been subjected to massive wear and tear, maybe putting themselves at risk of injury should they prioritize heavy lifting as a means of inducing muscle hypertrophy. But their training experience and existing levels of strength mean they can benefit enormously from methods that trigger high levels of metabolic fatigue, without risking injury or damage to their body.

Since the majority of beginners should prioritize lifting technique and building strength, this article is more relevant for the intermediate and advanced lifters who have already build a firm foundation of strength and wish to push muscle growth to the next level.

Re-Thinking Muscular Tension

The more muscle fibres you can recruit during a contraction, the more tension you will create, and the greater the stimulus for hypertrophy.

One way to do this is to simply lift heavier weights.

However, this is something that stronger and more experienced lifters may wish to purposefully avoid because, as previously mentioned, this can be a risky strategy and expose the lifter to a greater likelihood of injury. Secondly, a lifter must perform fewer reps with heavier loads, the lifter will need to perform more sets in order to meet the volume required for growth, which can substantially increase the session during, and may not be the most economical use of training time.

So how can sub-maximal loads be used to generate maximal muscle tension?

One very popular way is to slow down lifting speed and establish a solid mind-muscle connection i.e. focus on the working muscle and increase the intensity of the contraction during each repetition.

Whilst this is an effective method, it’s generally more suitable for isolation-based exercises where there is only one muscle to focus on and less requirement to stabilize the weight.

Another way is to simply take a sub-maximal weight to failure. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that loads as light as 30% 1RM are capable of inducing hypertrophy in this manner (Schoenfield et al., 2015). However, taking a light load to failure will require a high number of reps (25+), which may not be desirable for some lifters.

But, there is another method that lends itself perfectly to multi-joint exercises.

Fatiguing the muscle prior to performing a main exercise, can still allow you to increase its size, but with a smaller working weight and without having to perform a high number of reps in one single exercise.

Using a lighter weight means less stress on the body and may even provide some psychological relief as you don’t need to lift as heavy.

This is known as the ‘pre-fatigue’ method and has been exposed by bodybuilders since the 1970s.

But can you build as much muscle?

Let’s see what the science says.

How Effective Is The Pre-Fatigue Method?

A study by Júnior et al. (2010) investigated the effects of the leg extension prior to the leg press on motor unit recruitment in the vastus lateralis muscle.

In the study, the subjects were tested under 3 conditions:

- 15 reps x leg extension at 30% 1RM + 15 reps x leg press at 60% 1RM (low-intensity)

- 15 reps x leg extension at 60% 1RM + 15 reps x leg press at 60% 1RM (high-intensity)

- 15 reps x leg press at 60% 1RM (control)

Try our 1RM Calculator.

There was an increase in muscular activity during the leg press of 67.36% and 59.46% in the low and high intensity conditions, respectively.

The control group only showed an increase of 27.61%.

This suggests that lighter weights may be more effective at enhancing motor unit recruitment and play a role in ‘activating the muscle’ prior to working sets with heavier weights.

Whilst not tested, it would have been interesting to see the change in muscular activity levels in the high-intensity group if a lower % of 1RM had been used in the leg press.

A conflicting study by Augustsson (2003) demonstrated decreased muscular activity in the leg press following a set of leg extensions to failure. However, in this study, the subjects were using a 10RM load in the leg press, which was determined in a non-fatigued state. This suggests is that, if you were to use the pre-fatigue method, it’s probably beneficial to lower the weight in the main exercise.

In one longitudinal study, the pre-fatigue method was revealed to produce no advantage over conventional lifting for producing increases in muscle mass (Fisher et al., 2014).

In this study, a single set of an isolation exercise was used to take a muscle to absolute failure before performing a compound exercise.

However, this study used subjects with only a limited amount of training experience and a poor training protocol.

Another study by Trindade et al. (2019) used subjects with a slightly higher training age and also compared the effects of the pre-fatigue method vs. traditional training.

In this study, the subjects in the pre-fatigue group performed a single set of leg extensions to failure, followed by three sets of the leg press to failure with 75% 1RM, whereas the traditional training group only performed the leg press.

As you could expect, the pre-fatigue group performed fewer reps in the leg press, which resulted in an overall lower training volume over the study duration.

Interestingly, the subjects in both groups generated similar increases in hypertrophy.

Whilst it may be disappointing to hear that it’s not a superior method for building muscle mass, this study suggests both methods can be used to produce equal results.

Also, since subjects experienced a similar amount of hypertrophy, despite having used a lower training volume, it helps support pre-fatigue as an effective method for building muscle at lower intensities in the main exercise, without having to perform more reps.

Whilst it may be an inferior method to build maximum strength, it doesn’t appear to harm your muscle growth, and maybe a fantastic way to spice up your training routine from time to time.

Pre-Fatigue Methods

There are 2 ways you can used the pre-fatigue method in your training: –

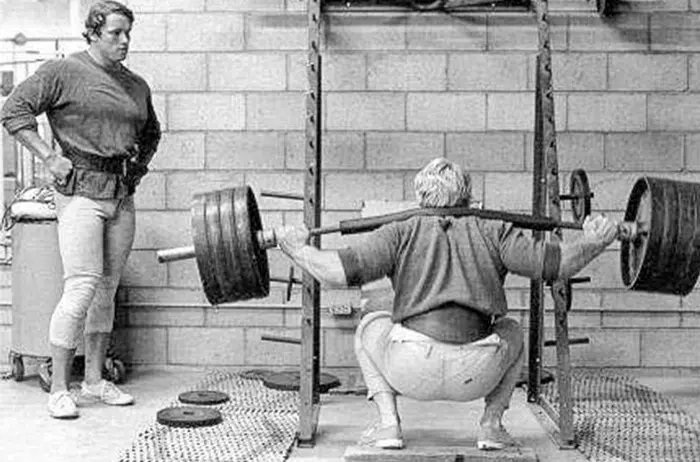

- Superset a single joint exercise with a compound exercise i.e. perform a set of the single joint exercise, such as leg extensions, and then go straight into a set of a compound exercise, such as squats or leg press

- Separate the two exercises i.e. perform all your sets of the single joint exercise and then do your sets of the compound exercise.

The science doesn’t favour one method over the other, so feel free to experiment.

Furthermore, the preceding exercise doesn’t need to be a single joint exercise, and in some cases, it may be more beneficial to use another multi-joint exercise, but one that uses a much lower intensity.

For example, prior to performing squats or the leg press, you could do 2-4 sets of:

- Leg extensions

- Bodyweight leg extensions

- Sissy squats

- Step ups

- Lunges

- Split squats

There’s also nothing stopping you from performing more than one exercise as part of your ‘pre-fatigue’ routine.

For example, if you wanted to really hammer all the working lower body muscles used in the squat prior to performing a squat, you could do the following: –

A) RFE DB Split Squat – 3 x 10/leg

B) Leg Extension – 3 x 15

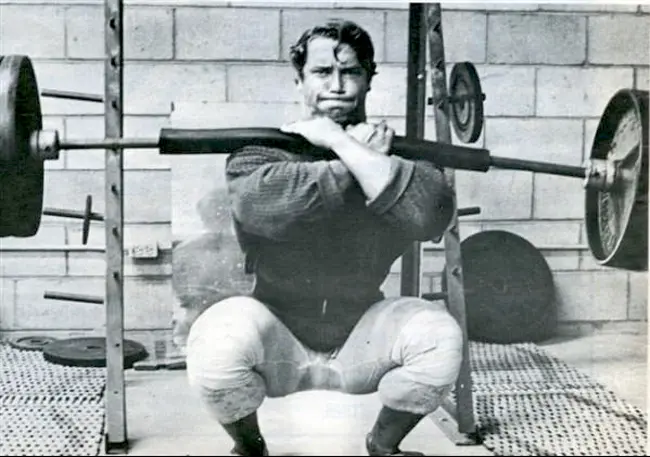

C) Barbell Back Squats – 4 x 6

Yes, by the time you get to the squats, you will almost certainly need to use a lower working weight than you are used to, but as the study by Fisher et al. demonstrated, this doesn’t mean you’ll be missing out on any muscle growth.

Summary

If you’re looking for a simple way to freshen up your training and enhance the size of your lower body, without resorting to more nauseating methods that leave you in a broken heap on the floor, then give the pre-fatigue method a try.

This involves performing sets of a single joint and/or lower intensity exercise prior to your main exercise.

You can either choose to do the sets immediately before, for example:

15 reps of the leg extension, followed by minimal rest and then straight into 6 reps of the squat.

Once you’ve finished the set of squats, you rest 1-2 minutes and then repeat the whole process for a total of 3-4 sets.

Or you can do all sets of the single-joint exercise separately and perform the compound exercise after.

So you could perform 4 sets of 15 reps in the leg extension, with 1-minute rest in between sets.

After your final set, you move onto the squat and perform 4 sets of 6 reps, with 1.5-2 minutes rest in between sets.

Choose whichever method is most practical and efficient for you and watch your dormant leg muscles grow.

References

- Schoenfeld, Brad J. “The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 24.10 (2010): 2857-2872.

- Schoenfeld, Brad J., et al. “Effects of low-vs. high-load resistance training on muscle strength and hypertrophy in well-trained men.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 29.10 (2015): 2954-2963.

- R Júnior, Valdinar A., et al. “Electromyographic analyses of muscle pre-activation induced by single joint exercise.” Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy 14.2 (2010): 158-165.

- Augustsson, J., et al. “Effect of pre-exhaustion exercise on lower-extremity muscle activation during a leg press exercise.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 17.2 (2003): 411-416.

- Fisher, James Peter, et al. “The effects of pre-exhaustion, exercise order, and rest intervals in a full-body resistance training intervention.” Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 39.11 (2014): 1265-1270.

- Trindade, Thiago Barbosa, et al. “Effects of Pre-exhaustion Versus Traditional Resistance Training on Training Volume, Maximal Strength, and Quadriceps Hypertrophy.” Frontiers in Physiology 10 (2019).

Tip: If you're signed in to Google, tap Follow.