Rest is an unavoidable part of working out. Because of limited energy, you need to take a break between sets to allow your muscles to recover so that you can attack your next set with maximal intensity.

When deciding how long to rest, the basic rule of thumb is the more challenging the set and the heavier the weight, the longer you need to rest. Hard/heavy exercise takes a lot out of your muscles and nervous system, and so you’ll need several minutes to regain the necessary energy to repeat the same effort.

In contrast, an easy/light exercise takes a lot less out of your muscles, and so they won’t need as long to recover.

A lot of exercisers use intuitive inter-set rests. In other words, they rest for as long as they think they need to between sets. While this approach can work, it’s not always the best. After all, it’s very easy to under or overestimate time, and resting too little, or too much could undermine your progress.

In this article, we discuss how long you should rest between sets and how to best manage your rest periods.

Inter-Set Rests by Training Goal

For best results, your workouts should match your goals. This is called the principle of specificity. According to this physiological rule, your body adapts to the type of training you do. Fitness experts call this SAID, which is short for Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands.

The SAID principle means that if you want to get stronger, you need to lift heavy weights. But, if you’re going to improve your cardiovascular fitness, you need to do plenty of aerobic training.

The length of time you rest between sets should also match your training goal. That’s because if you rest too long or not long enough, you may not be able to train optimally for your workout goal.

The accepted inter-set rest periods by goal are:

Rest Time Between Sets for Muscular Endurance

Muscular endurance is the ability of your muscles to generate low amounts of force for an extended period, e.g., 20-reps of push-ups.

Long sets like this cause a buildup of muscle-burning lactic acid. Brief rests allow lactic acid to dissipate enough that you can do another set but also train your body to deal with lactic acid more effectively.

Muscular endurance training is usually associated with short rests, typically 30 to 60 seconds between sets.

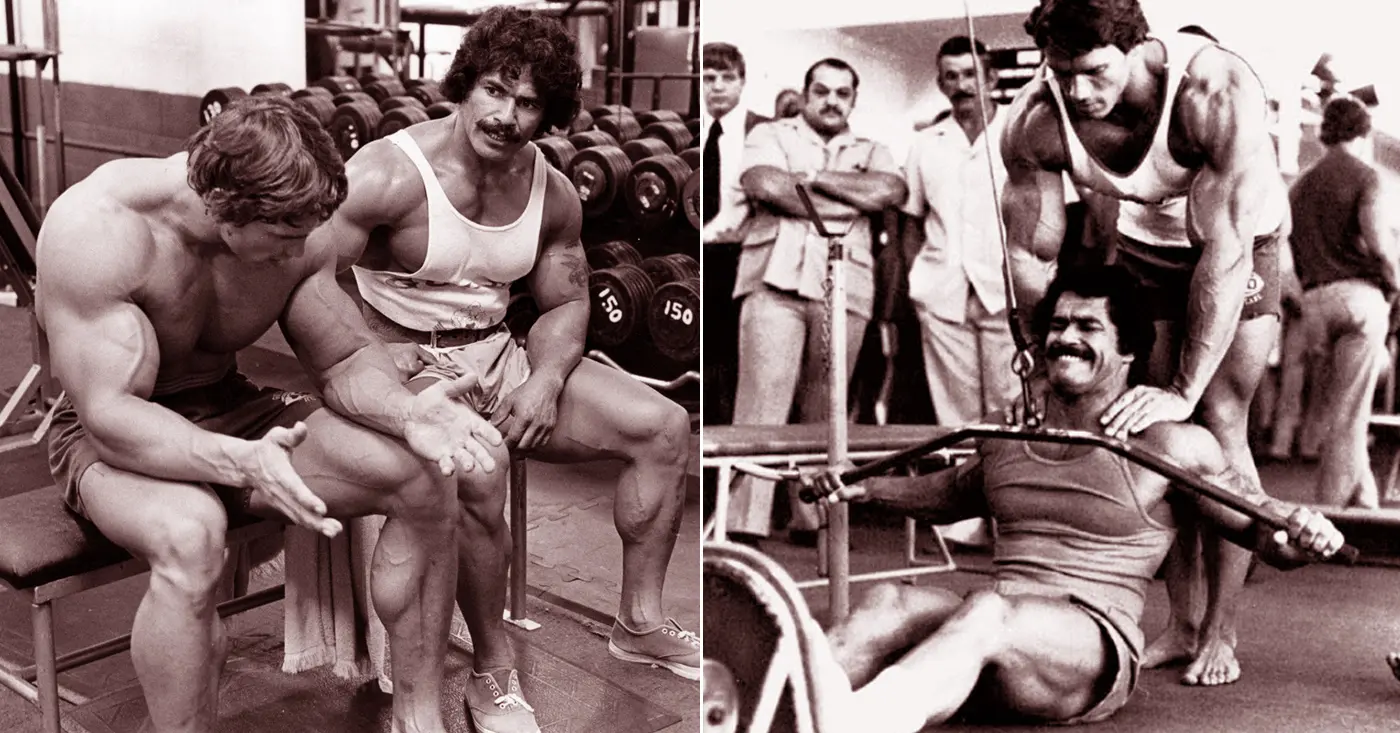

Rest Time Between Sets for Hypertrophy

Hypertrophy or bodybuilding-type training is all about making muscles bigger with less of a concern for strength or performance.

Using moderate weights and medium reps, rest periods for hypertrophy training are commonly limited to one to two minutes between sets. Heavy exercises such as bench presses and squats usually need two minutes, while less demanding exercises such as ab crunches and calf raises only need one.

Like endurance training, this allows lactic acid levels to dissipate and allows the muscle fibers themselves to recover so you can handle heavier weights.

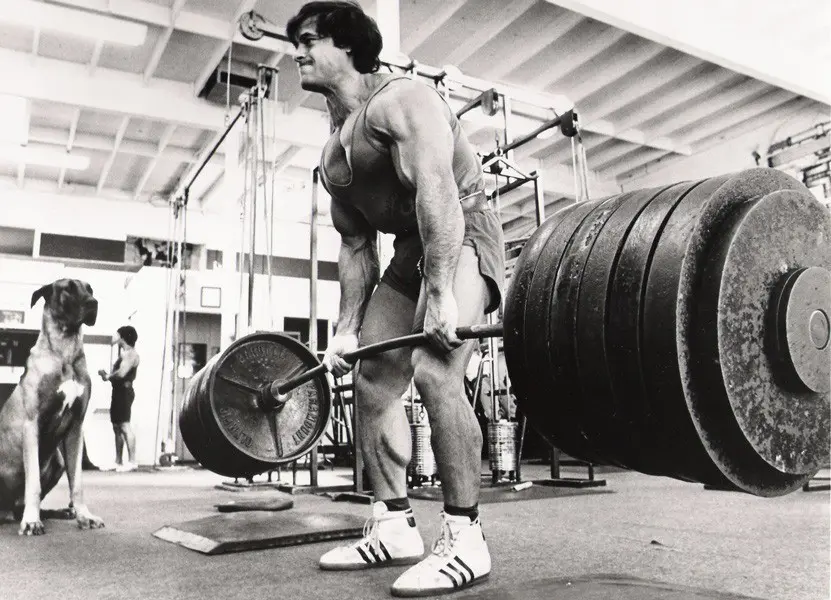

Rest Time Between Sets for Strength and Power

Strength and power training is all about maximal effort, and maximal effort is only possible when muscles and the nervous system are fully rested. Because of this, rests between sets are usually three to five minutes or even longer to allow for a full recovery.

There is little or even no real buildup of lactic acid during this type of training as sets are very short. However, the nervous system that governs muscle contractions takes much longer to recover. If maximal weights are to be lifted (strength) or weights are to be lifted as fast as possible (power), the nervous system must be well recovered.

To summarize:

| Training Goal | Endurance | Hypertrophy | Strength/Power |

| Intensity | Low | Moderate | High |

| Load | <67%

of 1RM |

67-85%

of 1RM |

>85%

of 1RM |

|

1RM (1-repetition maximum) = The maximum amount of weight that can be lifted once but not twice |

|||

| Repetitions per set | 13-20 | 6-12 | 1-5 |

| Recovery between sets | 30-60 seconds | 1-2

minutes |

3-5 minutes+ |

Exceptions

These guidelines provide a good starting point for most exercisers but, in several cases, it may be necessary to modify them…

Very fit people may be able to push themselves so hard that they simply cannot recover in the specified time because they are able to fatigue their muscles so completely. This is especially true when training for pure strength, where rests can be as long as 10-15 minutes between sets. Very hard workouts that involve maximal effort or attempts to set personal records will definitely benefit from longer than typical rest periods.

Conversely, being very fit may also mean that exercisers recover more quickly between sets. High levels of aerobic fitness make for fast and efficient clearance of lactic acid. This is especially true for hypertrophy and endurance-type training.

For very unfit people, poor cardiovascular fitness may mean that longer rests are necessary between sets of resistance training exercises. For example, a set of 15 bodyweight squats, which is technically muscular endurance training, may leave the exerciser very out of breath and necessitate a longer rest than usual. As the exerciser gets fitter, they should gradually shorten their rests, so they eventually match the recommended 30 to 60 seconds.

Rest can also be purposely cut short to increase the intensity of a workout. For example, while 30 to 60-second rests are the norm for muscular endurance, 20-second rests would make an endurance workout much more challenging and potentially more productive. Reducing rest times is an excellent way to increase workout overload without increasing the reps or the weight lifted.

Shorter than average rests also add an element of cardiovascular fitness to resistance training workouts, and while muscular performance may be compromised as a result, there is likely to be an increase in both energy cost and aerobic fitness as a result.

What About Rest Between Exercises?

Rests between exercises should be similar to the rests between sets, although they are not as important. The main thing to understand is that very long transitions between activities are a waste of valuable training time, and you could cool down too much if you dilly-dally excessively, which could necessitate another warm-up. Move quickly from one exercise to another, but there is no need to rush.

Passive vs. Active Inter-Set Rests

Surprisingly, there are two types of rest – passive and active. Passive rest involves doing nothing other than sitting or standing and waiting for your body to recover. You can use this time to change your weights, grab a drink, record your last set in your training diary, or just relax and chill. And yes, you may even have time to update your Facebook training status (#swole, #killing it, #king of the gym, etc.)!

Alternatively, you can use this downtime more constructively. Considering that you’ll probably spend longer resting than training per workout, active rests are a good way to make better use of your time.

Examples of active rests include:

- Stretching

- Pre-hab or re-hab exercises

- Short bouts of cardio

- Warming up for your next exercise

- Doing a secondary exercise (i.e., supersets)

If you are short of time, active rest periods allow you to get more done per training session. Simply slot a beneficial activity between sets of your main exercise instead of sitting and watching the clock.

Interval Training Rest Periods

If you do cardio, either for fitness or fat loss, you probably do interval training. Like strength training, intervals involve periods of work alternated with periods of rest. The length of time you rest between intervals will have a significant effect on your workouts.

The Energy Systems – A Brief Overview

Your body uses a chemical called adenosine triphosphate for energy, known as ATP for short. ATP can be produced aerobically or anaerobically, i.e., with or without oxygen. There is one aerobic energy system and two anaerobic energy systems.

While all three systems work together, the amount of work each one does depends on how quickly you need to supply your muscles with ATP.

During very high-intensity activities like sprinting and weight training, your body needs energy in a hurry. ATP is either supplied by chemical stores within your muscles or by partially breaking down glucose in an anaerobic environment. The two anaerobic energy systems are the ATP-CP system and the lactic acid system.

In contrast, during lower intensity activities such as jogging or easy cycling, your body needs less ATP and breaks down fat and glucose for energy in the presence of oxygen. This is called the aerobic system.

By using specific work-to-rest periods, it is possible to target each energy system individually. Because of this, when planning your interval training workout, you should always use a timer. This will ensure that your work-to-rest periods match your current training goal.

ATP-CP System Intervals

The ATP-CP energy system provides energy for very high-intensity activities like flat-out sprints. In intensity terms, we’re talking 95-100% of maximal effort.

This system relies on the ATP stored in your muscles. This is a very limited source of energy and only lasts around 10 seconds. The good news is that, because of creatine phosphate, which is the CP in the ATP-CP energy system, energy is quickly replenished so you can soon get back to work.

The ideal work-to-rest ratio to target the ATP-CP system is 1:6. As the ATP-CP system can only work for about 10 seconds, this means 10 seconds of work and 60 seconds of recovery.

Example workout: Using a rower, sprint flat out for ten seconds, row slowly to recover for 60 seconds. Repeat ten times.

Lactic Acid System Intervals

The lactic acid system, also called the anaerobic glycolysis system, produces energy from muscle glycogen – the stored form of glucose. In the lactic acid system, glycogen is broken down anaerobically, which creates lactic acid. Rapidly increasing lactic acid levels will eventually force you to stop exercising by causing fatigue and muscle pain.

The lactic acid system fuels high-intensity activity and lasts from 30 seconds up to two minutes, depending on how hard you are working. While the lactic acid system is involved in most types of exercise, it is most active when you are working at 80-95% of your maximum.

The ideal work-to-rest ratio to target the lactic acid system is 1:2 to 1:4.

Example workout: Peddle hard on an assault bike for two minutes, walk or jog for four minutes, and repeat five times.

Aerobic System Intervals

The aerobic or oxygen energy system uses glucose and fat for energy, which are metabolized in the presence of oxygen. The aerobic system is your default energy system as it’s what your body uses at rest and to recover from more intense bouts of exercise.

Because you have an abundant supply of both fat and glucose in your body, the aerobic system has an almost unlimited energy supply. Aerobic energy system performance is only really limited by muscular endurance.

The aerobic system does most of its work during low-intensity activities at or below 60% of your maximum heart rate. However, as you cross this 60% threshold, the lactic acid system starts to help out and provide additional energy.

The ideal work-to-rest ratio for aerobic intervals is 1:1 to 1:0.5.

Example workout: Cycle at an easy pace for three minutes, slow down or stop for 1½ minutes, and repeat five times.

To summarize:

| Training Goal | ATP-CP | Lactic Acid | Aerobic |

| Intensity | High | Moderate | Low |

| % of max. heart rate | 95-100% | 80-95% | 60-80% |

|

Max. heart rate = 220-age |

|||

| Work to rest ratio | 1:6 | 1:2 to 1:4 | 1:1 to 1:0.5 |

Breaking the Rules

So, does this mean you have to adhere to these work-to-rest ratios whenever you do interval training? Absolutely not! Lengthening the work periods or shortening the rest periods will increase the overload on your chosen energy system. Manipulating the work-to-rest periods is one way to make your workouts more demanding.

Use your workout timer to add a few seconds to your work periods or shave a few seconds of your rest periods. Small but regular changes like this will ensure that you continue to get fitter. However, it’s important to understand that if you change the ratios too much, you may find yourself straying into the realms of a different energy system.

Do Rest Periods Have to Be Constant?

While there is nothing to stop you from using the same rest period for all your sets of a given exercise, you don’t have to. In fact, changing your rest periods could be very beneficial.

As you train, your muscles become more fatigued. This means that:

- Each subsequent set becomes harder

- You may need to reduce the weight set by set to keep your rep count constant

- You may need to do fewer reps per set

Manipulating your inter-set rest periods could actually make your workouts more productive, as you can change them according to your increasing levels of fatigue.

For example, instead of doing three sets of 10 reps, resting 60 seconds between sets, you could do something like this:

- 1st Set 10 reps – rest 60 seconds

- 2nd set 10 reps – rest 75 seconds

- 3rd set 10 reps – rest 90 seconds

By resting more as fatigue sets in, you’ll be able to maintain workout intensity and volume.

That doesn’t mean you HAVE to use flexible rest periods, but it’s something to consider if you find your performance drops off steeply from one set to the next.

How to Manage Your Rest Periods

If you’re going to control your rest periods more precisely, you need a way to do it. If timing your rests becomes more trouble than it’s worth, you’ll soon stop doing it. Good options include:

Set a timer – using your watch or phone, set a countdown timer for however long you need to rest. Hit the start button as soon as you finish your set and get back to work when it sounds.

The add-on method – look at the time when you finish your set. Add on however long you need to rest and then do your next set at that time. E.g., if you finish your set at 14:30 and 45 seconds, and you need to rest two minutes, start your next set at 14:32 and 45 seconds.

EMOM – EMOM stands for every minute, on the minute. This method is popular with CrossFit and can be used for both strength and interval training.

With EMOM, you start your set at the top of each minute. On completing your reps, whatever time left is your rest period. So, if it takes you 15 seconds to complete your set, you get 45 seconds of rest.

But there is nothing to say you can’t use longer EMOM periods. For example, you could set a timer, so it beeps every 90 seconds. If your set takes you 30 seconds to complete, you’d then have 60 seconds before your timer sounds again. Or, if you’re training for strength/power, you could set your timer so it alerts you every four minutes.

This method is ideal if you keep forgetting to start your timer at the end of each set, or your math sucks! Just set your timer to repeat and start your next set when you hear the beep.

Wrapping Up

Inter-set rest periods are an essential but often overlooked aspect of training. Rest too little, and your workout could end up being harder than it needs to be, and it could hurt your performance.

But rest too long, and you could end up wasting a lot of valuable training time, and you might reduce the overall intensity of your workout, making it less productive.

Of course, you can manipulate your rest periods to manage fatigue and regulate workout intensity, but most of the time, they should match your training goals.

References

Fitness Volt is committed to providing our readers with science-based information. We use only credible and peer-reviewed sources to support the information we share in our articles.

- McMahon S, Jenkins D. Factors affecting the rate of phosphocreatine resynthesis following intense exercise. Sports Med. 2002;32(12):761-84. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200232120-00002. PMID: 12238940. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12238940/

- Hultman E, Bergström J, Anderson NM. Breakdown and resynthesis of phosphorylcreatine and adenosine triphosphate in connection with muscular work in man. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1967;19(1):56-66. doi: 10.3109/00365516709093481. PMID: 6031321. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6031321/

- Schoenfeld BJ, Pope ZK, Benik FM, Hester GM, Sellers J, Nooner JL, Schnaiter JA, Bond-Williams KE, Carter AS, Ross CL, Just BL, Henselmans M, Krieger JW. Longer Interset Rest Periods Enhance Muscle Strength and Hypertrophy in Resistance-Trained Men. J Strength Cond Res. 2016 Jul;30(7):1805-12. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001272. PMID: 26605807. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26605807/

- Ahtiainen JP, Pakarinen A, Alen M, Kraemer WJ, Häkkinen K. Short vs. long rest period between the sets in hypertrophic resistance training: influence on muscle strength, size, and hormonal adaptations in trained men. J Strength Cond Res. 2005 Aug;19(3):572-82. doi: 10.1519/15604.1. PMID: 16095405. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16095405/

- Krzysztofik M, Wilk M, Wojdała G, Gołaś A. Maximizing Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review of Advanced Resistance Training Techniques and Methods. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Dec 4;16(24):4897. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16244897. PMID: 31817252; PMCID: PMC6950543. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6950543/

- Paz GA, Maia MF, Salerno VP, Coburn J, Willardson JM, Miranda H. Neuromuscular responses for resistance training sessions adopting traditional, superset, paired set and circuit methods. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2019 Dec;59(12):1991-2002. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.19.09586-0. Epub 2019 May 20. PMID: 31113178. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31113178/

Tip: If you're signed in to Google, tap Follow.