Have you ever noticed how children will instinctively squat while studying something on the ground, or even while resting?

Squatting is an instinctive movement that serves as an amazing resting position. It takes a lot of the body weight off the lower back muscles, providing a “seat” of sorts, a great relaxing pose in places where there is nowhere to sit.

Over time, however, our bodies become less adept at squatting. We struggle to maintain a squat for a long time, and it becomes uncomfortable.

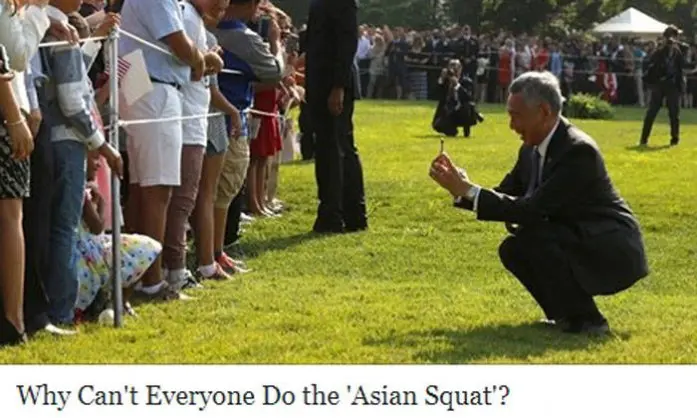

Why is that? And why is it that so many people from Asian countries can squat so comfortably for long periods at a time?

In this article, we’re going to look more closely at the Asian Squat: what it is, why it’s so comfortable for so many Asians, why Westerners can’t do it easily, and how you can train yourself to become more flexible and mobile in order to perform this movement.

In the long run, it’ll make you a much more limber person!

Level Up Your Fitness: Join our 💪 strong community in Fitness Volt Newsletter. Get daily inspiration, expert-backed workouts, nutrition tips, the latest in strength sports, and the support you need to reach your goals. Subscribe for free!

What is the Asian Squat?

The Asian Squat is a position similar to a deep squat:

Both feet are placed flat on the ground, with your knees spread slightly apart, and you squat down until your butt is resting on your ankles and calves.

Basically, they’re “sitting”, but instead of using a chair, they’re just sitting on the backs of their legs. It’s a highly relaxing position for those who have mastered it—and nearly impossible to do for people who haven’t spent their entire lives in the sitting position!

Why is the Asian Squat So Hard?

There are a number of reasons that non-Asians have a hard time with the Asian squat:

The wrong genetics:

Genetics do determine a great deal about musculature, mobility, joint range of motion, and balance. One informal study found that 100% of Asians examined were able to perform the squat, but only 13.5% of North Americans were able to. And of that 13.5%, 9% had some manner of Asian ancestry.

Genetics determine the proportions of our legs, which definitely affects squat performance. People with longer legs and shorter torsos will have a hard time with the Asian Squat, as will people with long upper legs (femurs) and shorter lower legs (tibia). These leg proportions will affect our balance and mobility. The fact that Westerners’ bodies have different musculoskeletal proportions than Asian bodies is one of the factors that contribute to our difficulty with the squat.

No practice:

Think about how much time you’ve spent in the squatting position since you were young. Over the years, you probably spent less and less time squatting, because it grew more difficult to maintain the squat. Eventually, you just stopped squatting altogether. The easy availability of chairs made it easy for you to find a comfortable seat without needing to squat. It’s very likely years have gone by since you last spent any serious amount of time squatting (outside the gym, of course!).

The lack of practice is definitely a prevalent factor. You can’t just take up Yoga and immediately master the difficult balance poses—like Crane or Royal Dancer—without practice. The same goes for the Asian Squat. It’s a movement that looks simple enough, but in reality, it requires a great deal of balance and stability that can only come through years of regular practice. For many Asians, it’s an everyday part of their lives. For Westerners, it’s something we have to make a conscious effort to incorporate into our lives.

Too much time spent sitting:

This is definitely one of the primary reasons that we struggle with deep squats—both the Slav Squat and Asian Squats (see below for the subtle differences between the two).

Many Asians squat to use the toilet, squat to relax, even squat to take a break and eat. Westerners, however, spend most of our time sitting. The fact that we spend so much of our time in chairs has led to physical changes in our bodies, specifically in our joints.

The synovial fluid in our joints is like “oil” that lubricates the joints to increase motion. The fact that we rarely use that full range of motion for the deep squat—because we can sit down—means that our bodies stop producing enough synovial fluid to enable that movement. By sitting, we have trained our bodies to adapt to a decreased range of motion. It becomes significantly harder to reach the full, deep Asian Squat because of this.

Age:

Children can squat easily and comfortably from a young age. This is because their bodies have a much greater range of motion, and their joints are still limber and loose. Over time, however, the squat becomes harder as our joints stop moving as easily (again, a likely side effect of all the time we spend sitting down). Age leads to a decreased range of motion, especially among those who don’t make it a point to train their mobility and flexibility.

By the time you reach your adult years, you’re likely experiencing more joint pain and stiffness (particularly after an intense workout or injury). Your joints work less efficiently as you age, due to a decrease in synovial fluid production. Without regular mobility training—or regularly squatting like so many Asians do on a daily basis—your joints just have a harder time reaching that full range of motion.

Asian Squat vs. Slav Squat: What’s the Difference?

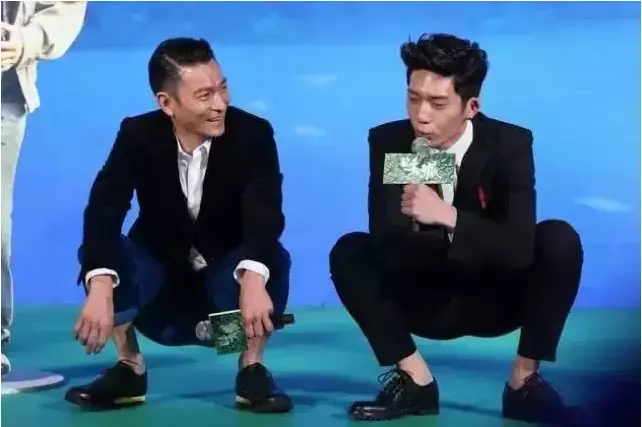

If you’ve spent any amount of time on the internet in the last few years, you’ll doubtless be familiar with the “Slav Squat”. Likely you’ve seen guys in tracksuits, gaudy jewelry, and heaps of attitude performing this squat as if posing for the cover of some Eastern European boy band album cover.

The Slav Squat is similar to the Asian Squat, in the sense that it’s utilized as a relaxing position to rest the body in lieu of a chair. However, it’s slightly different in terms of form and posture.

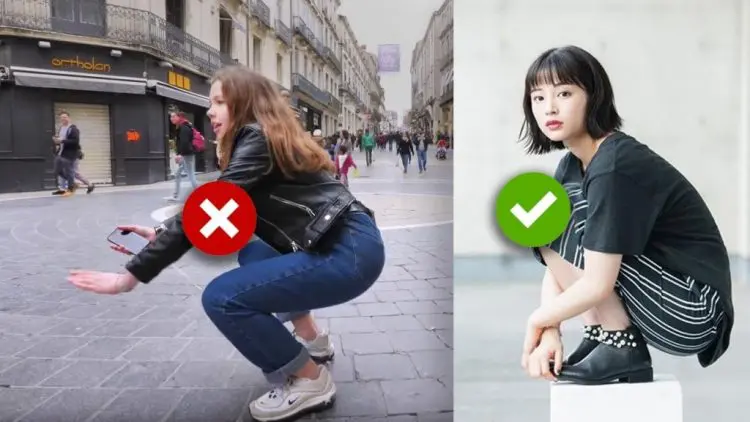

The Asian Squat

The Asian Squat is a very deep squat, performed with the feet flat on the floor, buttocks in line with the ankles, and your body balanced over the midline of your feet for stability. The feet are typically placed slightly more than shoulder width apart, with the toes either pointed forward or slightly outward.

This squat requires extreme ankle flexibility, as well as good balance to keep your center of gravity aligned over the midline of your feet to prevent toppling forward or backward.

Level Up Your Fitness: Join our 💪 strong community in Fitness Volt Newsletter. Get daily inspiration, expert-backed workouts, nutrition tips, the latest in strength sports, and the support you need to reach your goals. Subscribe for free!

The Slav Squat

The Slav Squat is very similar to the Asian squat, in the sense that it’s a deep squat that requires a great deal of flexibility and balance. However, while the Asian Squat typically keeps the feet closer together and the knees mostly aligned, the Slav Squat has a much wider base, with feet spread wider apart, and knees and toes pointing outward.

There are many Slavs who use the exact same posture as Asians, and the name “Slav Squat” is simply given due to the origin of the squat. However, a significant number of Slavs use this outward-pointed squat that provides a broader base of support for enhanced balance.

The Benefits of the Asian Squat

What makes the Asian Squat so beneficial? Why is it worth working toward mastering this incredibly difficult squat, one that most Westerners will struggle with?

Improved digestion

Specifically, the “elimination” part of the digestive process. Squatting helps to squeeze food through your digestive tract and out the “waste disposal exit” more effectively. That is one reason that so many Asian countries continue to use squat toilets despite the availability of modern sit toilets.

Enhanced posture

The Asian Squat encourages better spinal alignment, and improves your posture throughout your entire body. It also provides more mobility than simply sitting down and decreases the slouching, hunching, and sagging so common when sitting in comfortable chairs for long hours.

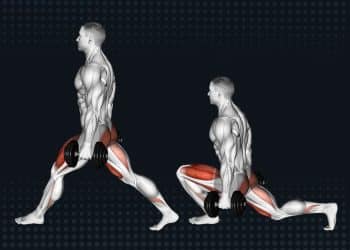

Better musculature

The fact that you’re squatting and standing repeatedly throughout the day engages your lower body muscles, building better leg strength. The act of squatting also requires your lower body stabilizer muscles to engage. Even your core grows stronger as a result of sitting in a squat position for extended periods of time.

Pregnancy aid

For millennia, women gave birth in a squatting position because it encouraged better muscle contraction and aided in the delivery. Squatting during pregnancy can reduce pressure on the uterus and strengthen the muscles that will be doing the hard work during childbirth.

Increased circulation

The repeated up-and-down of squatting will encourage better blood flow throughout your body, particularly your lower body.

Longer life

The European Journal of Preventive Cardiology created a sit-rise test that correlated with lower mortality rates. The test was a functional assessment of overall health and musculoskeletal fitness.

People who had an easier time rising without relying on their hands or elbows for support had a longer life expectancy than those who needed to support themselves. This increase in flexibility and mobility is believed to mark better overall health, which contributes to a longer lifespan.

Convenience

No matter where you are, you’ll always have a comfortable “seat”. You can relax and take a load off even if there are no chairs or couches around.

Risks of the Asian Squat

Now, it’s important to know that the squatting position isn’t entirely perfect. There are a few downsides to sitting in an Asian Squat for long periods of time:

- Numb legs

- Dizziness when you stand

- Potential knee and kneecap strain

- Cramps and stomach pain among pregnant women

However, for the short-term, it’s absolutely worth mastering the Asian Squat to improve your mobility and flexibility!

How to Do An Asian Squat

To get started practicing the Asian Squat, here’s what you need to do:

Step 1: Choose the right location. Look for a place that has something around waist-height to hold onto: i.e. a window, a bar, a table, etc. Stand in front of the object that you’ll hold onto, and make sure it’s within easy reach.

Step 2: Set up right. Plant your feet slightly more than shoulder-width apart, and point your toes slightly outward. Grip the handle tight and get ready to sit.

Step 3: Lower slowly. Holding on for support, lower your weight slowly until you’re “sitting”. You should try to find your balance, but focus on going as low into the squat as possible. Your buttocks should be close to touching your ankles, if not resting on the backs of your legs. That’s when you know you’re low enough!

Step 4: Hold. Hold the position for 10 to 20 seconds. Make sure your heels stay flat on the floor and keep your buttocks as low as possible.

Step 5: Stand up. This is going to be tough for beginners, and you’ll likely need to help by pulling yourself up to a standing position. Your thigh muscles will do most of the work of rising from the deep squat.

Step 6: Rest and repeat. Give your legs a minute or two to relax, then repeat the deep squat. Aim for three squats per day, 10 to 30 seconds per squat. Increase both the frequency and duration regularly until you see improvement.

Step 7: Move away from support. As you master the squat position, try to let go of whatever is supporting your weight. Focus on maintaining your balance on your own. Eventually, you’ll be able to sit without hanging onto anything.

Conclusion

The Asian Squat is an amazing technique that demonstrates excellent lower body flexibility, mobility, and strength. If you want to improve your posture and stretch out the important leg and feet joints, it’s worth practicing this squat every day.

It’s going to take a lot of work and regular practice to master it, but over time, you’ll find that you move much more easily and have significantly greater flexibility as a result.

Interested in measuring your progress? Check out our strength standards for Squat.

I find that doing theses squats in the pool or hot tub produce amazing relief for my low back pain!

I’m 77 and have had a hip re-surfacing procedure about 5 years ago. I did a few Asian squats and the hip became sore..Knees popped once or twice..I plan to ask my surgeon if this is ok and next time I try this I will do only one or two and do everything more gradually..Any thoughts?

Thanks for sharing your experience. Consulting your surgeon is the right step, as they can best advise on your specific situation. Taking a gradual approach to new exercises is important for preventing injury. Consider consulting a physical therapist or personal trainer to develop a safe exercise routine tailored to your needs. Best of luck!