In 2019 bodybuilding is a sport spoiled for choice. Visit any IFBB show and chances are you’ll find some of the largest lifters you’ll ever see. Go to the Mr. Olympia contest and the stage will host five, if not ten, ‘mass monsters’ competing in the heavyweight division. When everyone is a mass monster, it becomes harder to stand out from the crowd and even harder to build a legacy.

This was not always the case. When he burst onto the scene in the early 1960s, Sergio Oliva’s physique immediately distinguished him from his competitors. Bodybuilders spoke in awe of his ability to double in size when pumping up backstage. His narrow waist, large arms, and incredible back development served to make Sergio, or ‘The Myth’ as he was known, one of the greatest bodybuilders of his time and one of the first to wow audiences with his sheer size.

Sergio was the only bodybuilder to beat Arnold Schwarzenegger at the Mr. Olympia and for a certain generation of lifters, The Myth was the epitome of bodybuilding perfection. In today’s article, we examine Sergio’s eventful life from the Cuban military to the Olympia stage. Along the way, we’ll explore the foods and workouts which made The Myth’s body a thing of wonder.

Early Life

Sergio was born in Cuba on July 4, 1941. Now for those new to Cuban history, which included me five minutes ago, this meant that Sergio came of age at the precise moment Fidel Castro sought to overthrow Fulgencio Batista’s military dictatorship and replace it with his own communist regime. From 1953 to 1959 war raged across Cuba. (1)

Initially, Sergio was immune to the conflict, having spent the first twelve years of his life working on his father’s sugar cane fields in Guanabacoa. When he turned sixteen, Sergio’s father encouraged him to enlist in Fulgencio Batista’s military. Too young to fight, Sergio was allowed to enlist after his father convinced the recruiting officer that Sergio was eighteen. When it became clear that he had picked the losing side, Sergio found himself without direction.

Salvation soon came, however, in the form of weightlifting. Relaxing at a local beach, Sergio was invited to join a neighborhood weightlifting club by a passer-by impressed with his physique. It quickly became clear that Sergio was made for the iron game. (2) After six months of training, Sergio was clean and jerking over 300 lbs. As a middle-heavyweight, Sergio soon boasted a total of 1000 lbs. in the three Olympic lifts, the Clean and Jerk, the Snatch and the Military Press.

It was for this reason that Sergio was chosen to represent Cuba at the 1962 Central America Games in Kingston, Jamaica. In fact, the Union Deportiva de Cuba Libre, 1963 listed Sergio as Cuba’s best middle-heavyweight lifter. (3) At the Games, Sergio took second place but it was not his weightlifting exploits which caught the public’s attention. During his time in Jamaica, Sergio evaded his Cuban handlers and ran towards the American consulate. Safely within the consulate, Oliva was granted asylum in the United States where his life took an entirely different direction. (4)

Sergio Comes to America

Like many other Cuban exiles, Sergio first arrived in Miami where he spent a short while working as a TV repairman. On the advice of some close friends, he next moved to Chicago in 1963 where he spent the next several decades. In Chicago, Oliva divided his time between the Duncan YMCA and a local steel mill. (5) Working 10-12 hour shifts before training, Oliva was initially interested in being an Olympic weightlifter. Strange as this may seem given his later bodybuilding career, there was a good reason for Sergio to continue weightlifting.

From the late 1930s to the late 1950s, Weightlifting was one of the United State’s most popular, and successful, Olympic sports. By the time Sergio entered the US in 1962, America had dominated the medal board at the Olympic games for two decades under the coaching of Bob Hoffman. A new challenger emerged in the late 1950s with the rise of the Soviet Union. This meant that the US was desperate for new weightlifters like Sergio. There was just one problem, weightlifting was an amateur sport which meant that there was no money for the athletes. (6)

Previously Bob Hoffman avoided this problem by hiring American weightlifters as employees in his York Barbell company. No such offer was open to Sergio. Reflecting on this period in his life, Sergio later claimed that he moved from weightlifting to bodybuilding because bodybuilding offered some money in the form of prizes. (7) In this regard, it is likely that Sergio’s new gym in Chicago influenced his decision. Aside from Sergio, the Duncan YMCA gym was also home to Bob Gajda, the 1966 Mr. America winner who trained with Sergio.

With his mind made up, Sergio entered the Mr. Chicagoland contest in 1963, which he won. This was followed by the Mr. Illinois contest in 1964 and a seventh-place finish in the Mr. America contest. The next year, at the Mr. America contest, Oliva finished second and picked up the ‘Most Muscular’ award. It was here that the bodybuilding world first got a glimpse into Sergio’s outspoken side. At this time the Mr. America contest, then bodybuilding’s premier show, was based on a competitor’s physique, athletic prowess, and their personality. In effect, it was a Ms. America contest for male bodybuilders.

This unusual format often led to allegations of racism as black bodybuilders often finished second, having lost points on the personality scoring. (8) Sergio faced this exact problem in 1965 as evidenced by one judge’s claim that Sergio had ‘the outstanding physique of the meet’ but ‘had he been a citizen, and able to speak English fluently, he probably could have won the Mr. America title.’(9)

From Sergio’s memoirs we know how hurtful this decision was and when Sergio finished second again in 1966, he let his opinion be known. Congratulating the winner and his training partner Bob Gadja, Sergio told reports that ‘The AAU guys who don’t know the Civil War is over say Gajda is the winner when everyone in the house knew it was me.’(10) And in one fell swoop, Sergio defected from the AAU to Joe and Ben Weiders’ IFBB. Competing in the Weiders’ bodybuilding competitions, like the Mr. Olympia contest, Sergio’s bodybuilding celebrity took off.

Mr. Olympia Successes and Controversies

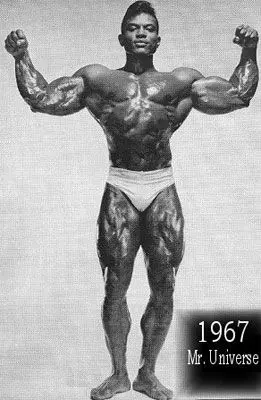

Sergio’s first experience of an IFBB competition came in 1966 when he finished first in the Mr. World competition. He then entered that year’s Mr. Olympia contest where he came fourth, a long way behind Larry Scott who picked up his second Olympia title. In the space of a year, Oliva went from a distant fourth to undisputed champion when he shocked the bodybuilding world in 1967. Easily winning the 1967 Mr. Olympia, Oliva’s size, muscularity, and definition was almost inconceivable to fans and judges alike. In the IFBB’s competition report, Wayne DeMillia wrote

In all the time I have witnessed and written about these events, I have always been able to pull some appropriate words from the gray matter to fit the occasion. Well, I give up. The words to describe Oliva haven’t been invented yet.

I may never again see such a display of muscle as long as I live. His musculature was an assault upon believability. At one time, he had size and shape but not much actual separation. Now things were different. In a year’s time, he had become the most phenomenal physical specimen I had ever seen.

As he swung from pose to pose, the excitement became almost violent. Hardly anyone could believe what they were seeing.(11)

The next year Sergio won the Mr. Olympia for the second time although under strange circumstances. There were no other contestants. As retold in Sergio’s memoir/training book, The Myth, his opponents failed to show up owing to injuries, business commitments or ill luck. This meant that despite being ‘big, muscular and cut’, Sergio’s victory was met with bemusement by many in the crowd. (12)

It was at the 1969 Mr. Olympia that Sergio solidified his legendary status by defeating Arnold Schwarzenegger in competition. In the months leading up to the Olympia, Joe Weider had excited bodybuilding fans about a young upstart named Arnold who would defeat ‘The Myth’ in competition. Reality proved different. Returning to Sergio’s writing, he remembered walking backstage in a butcher’s coat to hide his body from Arnold. Right before he went on stage, he threw the coat to one side, flexed his lats and completely demoralized Arnold. For the third year in a row, Sergio was the undisputed bodybuilding champion. (13)

Just as it looked as if Sergio would dominate bodybuilding for the foreseeable future, fortune turned against him. At the 1970 Mr. Olympia Sergio was defeated by Arnold Schwarzenegger. While few disputed Arnold’s victory, Sergio was incensed. Storming backstage, he claimed that Weider had fixed the competition so that Arnold, Weider’s favorite bodybuilder, would win. As happened with the AAU some years earlier, Sergio also claimed that Joe’s contest was racist towards a black bodybuilder. Sergio later claimed that ‘I was beaten by the judges and the Joe Weider IFBB organization. Not by Arnold.’ (14)

https://www.instagram.com/p/B4qbuY2HznB/

Regardless of whether or not he was correct, Sergio’s behavior marked a downward spiral in his bodybuilding career. The next year, at the 1971 Mr. Universe competition, Sergio finished second to Bill Pearl. Once more, Sergio cited institutional racism and criticized the competition organizers. This time Sergio found a supporter in Arthur Jones. Jones, who came to fame owing to his Nautilus machines and ‘High-Intensity Training’ theory, was then one of the most influential voices in bodybuilding. Surveying Sergio’s second-place finish, Jones claimed that an ‘outright screwing’ had kept Sergio from winning. Looking at competition footage of the ‘71 Universe, it is easy to see why Jones and Sergio were so animated. (15)

Later Life

If it’s not clear by now, Sergio had become something of a pariah in the bodybuilding world. His outspoken nature and refusal to accept the murkier sides of bodybuilding began to tarnish his standing in the sport. In 1971, Sergio was a guest poser at the Mr. Olympia competition having been temporarily banned for competing in the Mr. Universe contest. At that time, Joe Weider banned anyone who competed in non-IFBB competitions. Sergio demanded to pose at that year’s Olympia and Joe, rather reluctantly agreed. Sergio quickly won the crowd over and embarrassed Joe Weider in front of his public. (16)

The next year, Sergio exited the IFBB having finished second in the 1972 Mr. Olympia. Soon after, Sergio began competing with the newly created World Bodybuilding Guild (WBBG) and spent the next several years winning every WBBG show he entered. In the early 1980s, Sergio competed with the World Amateur Body Building Association (WABBA) and once more, dominated their shows. Although he was winning, Sergio was very much the forgotten man of bodybuilding. Not competing in the Mr. Olympia shows meant that Sergio was excluded from the sport’s most important contest.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B4E9SHVlZ0P/

In 1984, Sergio returned to the Mr. Olympia, a full twelve years after his last show. Having been promised by Joe Weider that the judges would be fair, Sergio was convinced to enter. Having disappeared, at least in the eyes of many fans, Sergio’s return was downright sensational. He still had the muscularity, definition, and size that shocked the sport in the mid-1960s. An eighth-place finish could not disguise the fact that Sergio had stolen the show. It was at this Olympia that Sergio earned himself the title of ‘The Eighth Wonder of The World.’ (17)

Sergio would return to the Olympia stage in 1985 where again, he finished in eighth. Any chances of Olympia glory in 1986 were denied when Sergio was shot five times by his wife in a domestic dispute. From 1986 to his death in 2012 from kidney problems, Sergio continued to train, write to fans and act as an informal ambassador of the sport. Although his bodybuilding record was marred by Sergio’s fractious relationship with contest organizers, few could dispute his greatness.

On hearing of Sergio’s death, his once fierce competitor Arnold Schwarzenegger wrote that

Sergio Oliva was one of the greatest bodybuilders of all time & a true friend. A fierce competitor with a big personality – one of a kind…(18)

There’s a reason Sergio was known as The Myth.

Sergio Oliva Training

As he progressed in his training, Sergio began to rely on his own instincts. Instead of entering the gym with a pre-planned routine, Sergio instead trained by instinct and feel. He would continue to work a muscle group until he was satisfied it had been exhausted. We know that Sergio was greatly influenced by his training partner in Chicago, Bob Gadja. Gadja, who won the 1966 Mr. America, demised his own workout system called peripheral heart action (PHA). (19) Practically speaking, PHA was based on full-body workouts with very little rest in between exercises. When training, this meant that Gadja, and by extension, Sergio would train intensely, moving quickly between exercises. Reading later reports from Sergio’s friends and training partners, The Myth would spend hours in the gym, barely taking time to talk to anyone and moving his way from exercise to exercise.

At the core of his philosophy was the importance of listening to his body. Throughout his training career, Oliva experimented with pretty much every style of training. He combined weightlifting and bodybuilding exercises, used Joe Weider’s drop set inspired training and even trained using Arthur Jones’ controversial High(hyphen) Intensity Training methods. In the end, and certainly, when he was training in the 1970s, Oliva was far more instinctive in his training. For example, Oliva rarely used rigid set structures in his training, preferring instead to train a body part until he was satisfied he had exhausted this muscle. So when training chest or legs, Sergio could use six sets one week and sixteen the next!

Additionally, Sergio’s range of motion was controversial for the time. Unlike others, Sergio often used partial reps with heavy weights. This was for reasons of practicality rather than any philosophical belief. After a decade or so of lifting heavy weights, Sergio began experiencing a great deal of pain in his elbows and knees. In a desperate bid to overcome this issue, Sergio used partial reps to save his joints.

Watching Sergio train in 2019, the partial reps add a certain rhythm to his approach.

Now for those interested in the nuts and bolts of a Sergio routine, the following workout from 1973 gives an insight into his training methods:

Monday: Chest, Back

A1. Bench Press, 8 sets x 8 reps (to 380 lbs)

A2. Chin-ups, Wide Grip, 7 x 5-15 (bodyweight)*

*With this superset, Sergio would start with 200 x 8 on the bench press and work up to 380 x 8. With the chin-ups, he would start with 15 reps and work down to 5 reps.

B1. DB Flyes, 5 x 15 (to 80 lbs.)

B2. Dips, 5 x 15 (bodyweight)

Tuesday: Shoulders, Biceps and Triceps

- Military Press, 5 x 15 (to 200 lbs)

- Barbell Curls, 5 x 5 (up to 200 lbs)

- French Curls, 5 x 5 (up to 200 lbs)

- Scott Curls, Barbell, 5 x 10 (to 160 lbs)

- Scott Curls, Dumbbells, 5 x 5 (up to 60 lbs)

F1. Seated Triceps Extension, 5 x 5 (50 lbs)

F2. Triceps Pressdown, 5×15 (no weight given)

Wednesday: Abs, Legs, Calves

- Sit-ups, 10 x 50

- Leg Raises, 5 x 20

- Side Bends with Bar Behind Neck, 5 x 200 reps

- Squats, 5 x 5 (to 480 lbs)

- Standing Heel Raises, 10 x 8 (to 300 lbs)

Thursday: Chest, Back, Shoulders

- Bench Press, 7 x 5 (to 380 lbs)

B1. Press Behind Neck, 5 x 5 (to 250 lbs)

B2. Rowing Machine, 5 x 5 (to 200 lbs)

C1. Seated Press with Dumbbells, 5 x 8 (to 80 lbs)

C2. Dipping Bar, 5 x 8 (bodyweight)

Friday: Arms, Back

- Military Press, 3 x 10 (to 200 lbs)

- Barbell Curls, 3 x 5 (to 200 lbs)

- French Curls, 3 x 5 (to 200 lbs)

- Scott Bench for Triceps, Barbell, 3 x 5 (to 200 lbs)

- Scott Bench for Triceps with Dumbbell, 3 x 5 (to 60 lbs)

F1. Tricep Press Downs, 3 x 15 (weights not provided)

F2. Chinning Behind Neck, 5 x 5 (bodyweight)

G1. Torso Machine, 5 x 10 (weights not provided)

G2. Lat Machine Pulldown, 5 x 10 (weights not provided)

Saturday: Abs, Legs, Calves

- Sit-ups, 5 x 10 (bodyweight)

- Leg Raises, 5 x 10 (bodyweight)

- Side Bends, 3 x 50 (bodyweight)

- Squats, 5 x 3 (to 400 lbs), 3 x 20 (250 lbs)

- Front Squats, 5 x 10 (to 200 lbs)

- Calf Raise, Seated, 5 x 5 (to 200 lbs) (20)

Feeding the Myth

I include a section on Sergio’s diet and nutrition beliefs primarily because it makes for fantastic reading. Sergio was, as any of his contemporaries would attest, incredibly hardworking. He was also genetically blessed in a way few of us can fathom. This meant that Sergio could really eat whatever he wanted and still maintain an Olympia winning physique. In later interviews, Sergio claimed that he didn’t need to diet so he’d eat everything in sight. This included gallons of milk, eggs, meat, pancakes, and even ice cream. When training, Sergio always had a thermos of coffee which he claimed gave him energy and made him sweat. (21)

The only time Sergio ‘dieted’ was for the 1984 Mr. Olympia when he followed the dietary advice of the equally legendary Frank Zane. The problem with this approach was that Zane’s body was drastically different from Sergio’s. Following Zane’s advice, Sergio got leaner but also lost a great deal of muscle mass. From Sergio’s later recollections the experience seemed miserable.

Nothing but fish and a lot of salads. Which was good because I always ate a lot of salads and vegetables. But I am a big eater. I have always been a big eater. So I was going to bed hungry and waking up hungry. So it was not for me. If it worked for Frank Zane, well good for him… (22)

Sergio, somewhat incredibly, appeared to function better eating everything in sight.

Remembering Sergio

Today fans of bodybuilding have taken a renewed interest in Sergio’s career owing to the exploits of his son, Sergio Junior. While Sergio Junior is only beginning to make waves in the industry, his early successes have reminded us all of his father. How then, can we describe The Myth? For me, Sergio senior is best seen as the original mass monster. The individual who came from nowhere and shocked the bodybuilding world.

In a sport defined by freakish and large physiques, Oliva was a step ahead of his competitors. He intimidated Arnold at the Olympia, inspired thousands and, in his own way, left his mark on the sport. The size of Sergio’s body, the narrowness of his waist and his spread of his back muscles served to create a body that few could explain, but all admired. It was, as Sergio later recorded, the result of hard effort and sheer determination.

Reflecting on his own success Sergio proved equally stunned with his own legend ability

Somehow it had to be something to do with my bone structure, genes, and many other factors and when I put it all together and trained the way I did … It was not easy. I trained brutal all my life. It was like an explosion and I was growing like a balloon. Boom, boom, boom like crazy.

When I was standing in front of the mirror when I was pumped and putting the baby oil on and everything (prior to going on stage in a bodybuilding contest) that was the only time I saw myself. And it was, “Oh my God, you really did it.” You walk out and you see the expression in the people’s eyes. But you don’t see yourself. I only saw it one time. And then I realized why people looked at me that way. (23)

There was a reason people called him ‘The Myth.’

References

- David Robson, ‘Memories of the Myth,’ Bodybuilding.com. Available at https://www.bodybuilding.com/fun/memories-of-the-myth-greats-pay-tribute-to-sergio-oliva.html.

- Norman Zale, ‘Sergio Oliva, Part One’, 1975 Article. Available at http://ditillo2.blogspot.com/2017/09/sergio-oliva-norman-zale-1975.html.

- Union Deportiva de Cuba Libre, Sports Without Freedom is No Sport at All: Communist Sports is a Political Instrument (Havana, 1963), 4.

- Sergio Oliva and Frank Marchante, Sergio The Myth (Gras Pub., 2007), 4-7.

- David Robson, ‘An Interview with the Myth,’ Bodybuilding.com. Available at https://www.bodybuilding.com/fun/drobson331.htm.

- John D. Fair, “Bob Hoffman, the York Barbell Company, and the golden age of American weightlifting, 1945-1960.” Journal of Sport history 14, no. 2 (1987): 164-188.

- Robson, ‘An Interview with the Myth.’

- John D. Fair, “Mr. America: Idealism or Racism: Color Consciousness and the AAU Mr. America Contest, 1939-1982.” Iron Game History (June 2003) 18.

- Ibid., 22.

- Ibid.

- Wayne DeMillia, ‘Mr Olympia 1967 Report,’ JoeWeider.com. Available at https://www.joeweider.com/2012/06/13/mr-olympia-report-1967/.

- Oliva and Marchante, Sergio The Myth, 34.

- Arnold Schwarzenegger, The new encyclopedia of modern bodybuilding (Simon and Schuster, 1998), 698.

- Oliva and Marchante, Sergio The Myth, 41.

- Arthur Jones, ‘My First Half Century in the Iron Game.’ ArthurJonesExercise.com. Available at http://www.arthurjonesexercise.com/First_Half/11.PDF.

- Oliva and Marchante, Sergio The Myth, 42-45.

- Robson, ‘An Interview with the Myth.’

- ‘A Tribute to Sergio Oliva,’ Ironman Magazine. Available at https://www.ironmanmagazine.com/sergio-oliva-tribute/.

- Conor Heffernan, ‘Bob Gajda’s Peripheral Heart Action Training,’ Physical Culture Study. Available at https://physicalculturestudy.com/2018/01/22/bob-gajdas-peripheral-heart-action-pha-training/.

- ‘Workout Systems: Mr. Olympia Sergio Oliva Workout,’ Poliquin Group. Available at https://main.poliquingroup.com/ArticlesMultimedia/Articles/Article/2744/Workout_Systems_Mr_Olympia_Sergio_Oliva_Workout.aspx.

- Robson, ‘An Interview with the Myth.’

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Tip: If you're signed in to Google, tap Follow.