After more than 30 years of working as a personal trainer, it’s safe to say I’ve tried and prescribed virtually every type of exercise you can think of. From kettlebell to dumbbell to barbell to suspension trainer exercises via steel maces, medicine balls, calisthenics, resistance bands, sandbags, and gymnastic rings—I really have used them all.

With this huge library of exercise options behind me, I always have the right tool for my clients’ training goals. Plus, knowing a lot of different exercises means I can keep my workouts fresh and interesting, which research suggests is critical for long-term adherence (1).

As such, I don’t tend to think of exercises as good or bad. Instead, I focus on risk vs. reward. Some potentially iffy exercises are worth doing because of the prospective payoff. Other exercises provide a poor return compared to their disadvantages and drawbacks and aren’t worth doing.

Of course, all this depends on what your tolerance for risk is and what you are training for.

With all that in mind, in this article, I share five exercises I rarely prescribe to anyone, as, in my opinion, the risks far outweigh the rewards, and there are safer, more effective alternatives.

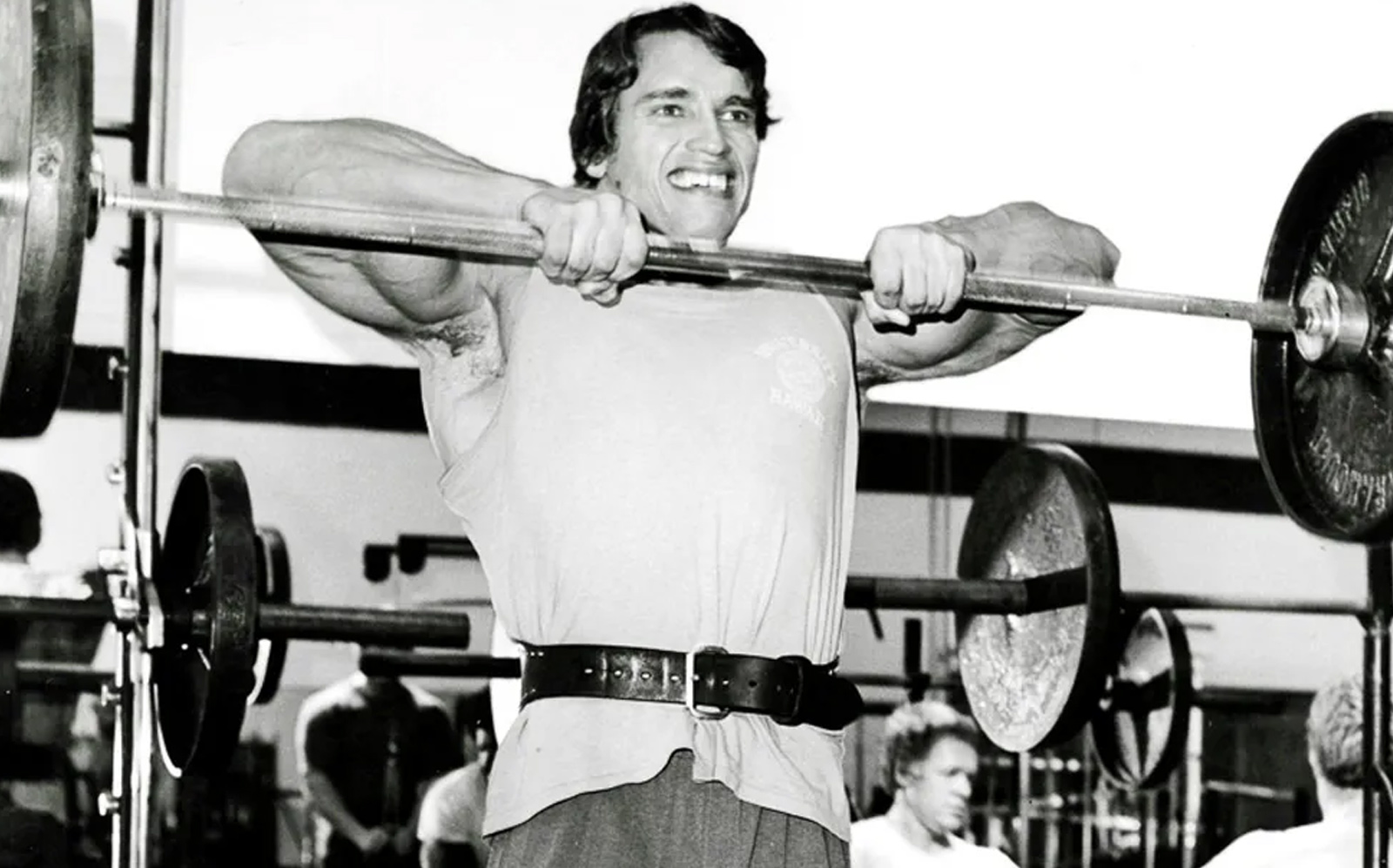

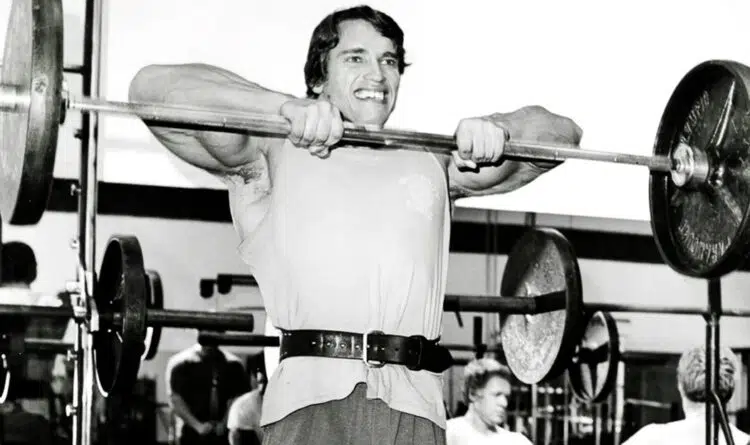

1. Upright Row

Purpose: Develop the upper trapezius and deltoids

The barbell, cable, banded, and dumbbell upright row is a popular exercise, especially among bodybuilders. Targeting the shoulders and upper traps, it can help develop that powerful “yoked” look that is popular among gym bros.

Upright rows are undoubtedly an effective exercise, and you can see the target muscles working. They involve elevation of your shoulder girdle, which hammers your upper traps, while your arms move up and away from your body in a movement called abduction, working your deltoids.

However, while it can help you build bigger shoulders and traps, it also has the potential to wreck your shoulder joints.

Given that your shoulders are involved in just about every upper-body exercise, it’s no exaggeration to say that chronic shoulder pain could significantly hamper your future progress and gains.

Upright rows involve simultaneous abduction, rotation, and compression of your shoulder joint, which puts tremendous stress on the shoulder joint capsule and the rotator cuff muscles. This movement is like trying to do squats while twisting your knees—sounds like a recipe for disaster, right?

So, while upright rows could give you the yoke you’ve always dreamed of, they could also destroy your shoulders and end your training career. The juice is definitely not worth the squeeze!

Better Alternatives:

Instead of training your deltoids and traps at the same time, it’s safer to work them independently. As such, better choices include:

- Dumbbell shrugs

- Trap bar shrugs

- Dumbbell lateral raises

- Cable lateral raises

- Dumbbell overhead presses

2. Hip Adduction/Abduction Machine

Purpose: To develop the inner and outer thighs.

Most gyms have hip adduction and hip abduction machines. They’re very popular with female exercisers as they target what are often perceived as “problem areas,” but men use them, too.

It’s not uncommon to see people pumping out dozens, if not hundreds, of reps as they try to trim and tone their legs.

Unfortunately, spot reduction is all but impossible, and, to make matters worse, these machines put a lot of shearing force on the hips and pelvis, which can result in both short and long-term injuries.

It’s for this reason that hip abduction/adduction machines are not recommended for pregnant and post-natal women, whose hips and pelvises are already overly mobile and unstable.

In addition, the hip adductor and abductor muscles don’t really work the same way as they do during these exercises. Rather, the abductors and adductors mostly function as stabilizers, especially when you stand on one leg or transfer your weight from one side to another, as you do when you walk or run.

Better Alternatives:

So, a high risk of injury and not a very effective movement, plus some people feel very self-conscious when using the hip adduction/abduction machine. Thankfully, there are plenty of better, safer, less compromising alternatives, including:

- Curtsy lunge

- Lateral lunge

- Booty band squat

- Rear foot elevated split squats

- Single-leg squat

3. Front Raises

Purpose: To develop the anterior/front deltoids.

Front raises are part of most lifters’ shoulder workouts. They target the anterior head of the deltoids, which is located on the front of your shoulders. Front raises can be done with dumbbells, a barbell, a cable machine, or resistance bands, and all of these variations are very effective.

However, just because an exercise works well doesn’t mean you should do it!

The anterior deltoids are involved in every horizontal and vertical pressing movement you perform. Whether you’re doing bench presses or shoulder presses, your front delts are already working hard.

As such, most exercisers have overdeveloped anterior deltoids already and training them with front raises just makes an already out-of-proportion muscle even bigger. Imbalances between the anterior, medial, and posterior deltoids can affect both aesthetics and shoulder function.

While bodybuilders may benefit from isolating and beefing up their front delts, recreational exercisers rarely need to train this overused muscle.

Better Alternatives:

Given how valuable your training time and energy are, it makes no sense to train a muscle that you’re already hammering with several other exercises. Rather, most lifters would benefit from less anterior deltoid training and more work for their medial (side) and posterior (rear) delts. Good exercises for this purpose include:

- Cable, dumbbell, machine lateral raises

- Cable, dumbbell, machine reverse flyes

- Face pulls

- Band pull aparts

- Victory raises

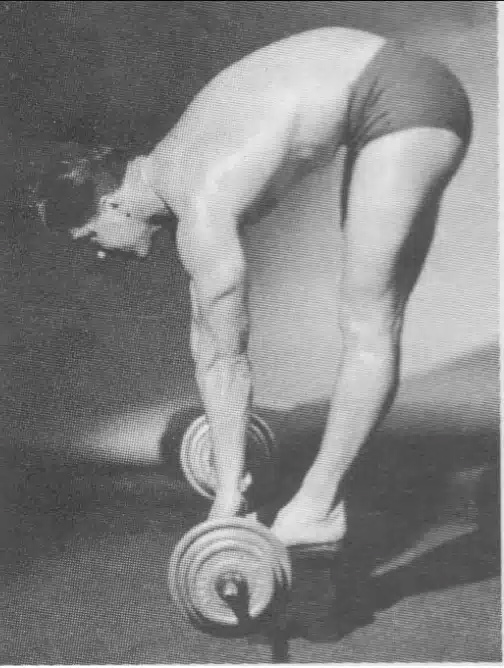

4. Straight Leg Deadlifts

Purpose: To develop the hamstrings.

As a former powerlifter, I have a lot of love for the deadlift and its many variations. I think that picking heavy weights off the floor is one of the best ways to build functional strength and a bulletproof back.

However, one variation I never prescribe or perform is the old-school straight leg deadlift.

Not to be confused with the stiff-legged deadlift or Romanian deadlift, where the knees are slightly bent, the straight leg version involves keeping your knees locked, and that’s a problem.

Locking your knees and hinging forward from the hips essentially deactivates your glutes, putting all that weight on your hamstrings and lower back. While this probably won’t hurt your hammies, it’s no surprise that straight leg deadlifts can cause back injuries.

Plus, if you have anything other than excellent hamstring flexibility, you’ll probably round your lower back as you lean forward, further compromising an already injury-prone body part.

Some exercisers do straight leg deadlifts while standing on a step, bench, or box so they can descend further. While this undoubtedly increases the stretch in your hamstrings, it also promotes even more lower back rounding.

A rounded lower back is a weak lower back, as stress that should be supported by your lumbar muscles ends up on your intervertebral disks and ligaments—structures that are easily damaged and slow to heal.

Better Alternatives:

Straight leg deadlifts aren’t an effective hamstring or lower back exercise and do very little for your glutes. They also place your spine in a compromised position, with a real risk of serious injury. Safer, more effective alternatives include:

5. Planks (The way that most people do them)

Purpose: To develop core strength and stability.

Planks are one of the most popular core exercises. They’re joint-friendly, require no equipment, and work almost every muscle in your body. But despite their many benefits, most people do them wrong.

The issue isn’t the plank exercise itself. Rather, it’s how people approach it.

Holding a plank for several minutes at a time with minimal muscle tension isn’t just boring; it’s a lousy use of your training time. If you can scroll your phone, chat with your gym buddy, or mentally write your grocery list while planking, you’re not working hard enough to see results.

A proper plank isn’t a passive exercise. You should be bracing your abs like someone’s about to punch you, squeezing your glutes hard, driving your elbows into the floor, and actively engaging your quads and lats.

When done correctly, a 20- to 30-second plank is more than enough. If you feel you can go for longer, you need to tense your muscles harder. This is a core strength exercise after all!

Instead of seeing how long you can plank for, try contracting your muscles harder and seeing how quickly you can exhaust them. This change in mindset will save you a ton of time while making your workout much more effective.

So, while planks aren’t inherently a waste of time, the way most people do them definitely is. More tension, not more time, is the secret to a strong, rock-hard midsection. Planking for more than a minute or two is very inefficient.

Better Alternatives:

Rather than chasing time, focus on more demanding, time-efficient plank variations or other high-tension core exercises, such as:

- RKC planks

- Plank with shoulder tap

- Plank to push-up

- Dead bug

- Hollow hold

Frequently Asked Questions

Whenever I suggest that a popular exercise might not be worth doing, it tends to ruffle a few feathers. I get it—some of these moves have been gym staples for decades. But I’m not here to rock the boat for the sake of it. Rather, I just want people to train smarter and avoid exercises that offer more risk than reward.

Here are three common questions I get whenever I suggest skipping these so-called “essentials.”

So, are you saying these exercises are bad for everyone?

Absolutely not! There are some people who can do these exercises without any issues or may need to do them because of their sport or fitness goals. All I’m saying is that for the average person, there are safer or more effective alternatives, that may be a better fit for your workouts.

I’ve been doing some of these for years without any issues—why stop now?

While I’m glad you haven’t had any issues yet, that doesn’t mean you won’t in the future. Wear and tear from training is cumulative and can take years or decades to become apparent. So, you could keep rolling the dice and hoping that your workouts aren’t doing you any below-the-surface harm or make changes now to avoid problems around the bend.

Don’t some of these exercises still have value for advanced athletes or bodybuilders?

Yes, but it all comes down to that risk vs. benefit continuum I talked about at the start of this article.

In some cases, e.g., elite athletes and hardcore bodybuilders, health risks are part and parcel of pushing your body to its limit. It’s what you have to do to succeed. But, if you are training for general health and fitness, the last thing you should do is train in such a way that you’re courting injury. Only you can determine if the risk is worth it.

Closing Thoughts

Choosing the right exercises for your workout isn’t about avoiding effort or challenge. It’s about training smart to maximize results and minimize injury risk. The five exercises I’ve shared here consistently offer more drawbacks than benefits for most people.

That doesn’t mean they’re universally “bad,” but safer, more effective alternatives exist.

So, I encourage you to reflect on your own routine and, if any of these exercises are staples for you, consider swapping them out for better options. Your body and your progress will thank you.

Ready to upgrade your workouts? Start by trying one of the safer alternatives today and see how much more effective your training can become.

References:

1 – Dregney TM, Thul C, Linde JA, Lewis BA. The impact of physical activity variety on physical activity participation. PLoS One. 2025 May 27;20(5):e0323195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0323195. PMID: 40424375; PMCID: PMC12112371.